Austen in Motion

UMBC’s annual Undergraduate Research and Creative Achievement Day (or URCAD) is always a date circled in red on the university calendar – and for good reason. This past April 22, more than 180 students in 28 majors – ably mentored by the university’s faculty – presented their scholarly work at locations across the UMBC campus.

At times, the work presented by undergraduates finds its energy by crossing over disciplinary boundaries. Such was the case with “Letters from Jane: A Tribute to Jane Austen,” a project conceived by Hannah Mary Rzasa ’10 and mentored by Doug Hamby, a professor in UMBC’s Department of Dance.

Rzasa’s project melded movement with literary study of the life and literary work of Jane Austen – specifically incorporating excerpts from letters between Austen and her sister, Cassandra, into the project.

“You will not expect to hear that I was asked to dance,” Austen wrote to her sister in 1809, in one of the letters excerpted by Rzasa. “But I was.” In Rzasa’s video project, Austen dances again, both in words and in Rzasa’s choreography of scenes from her life and untimely death in 1817.

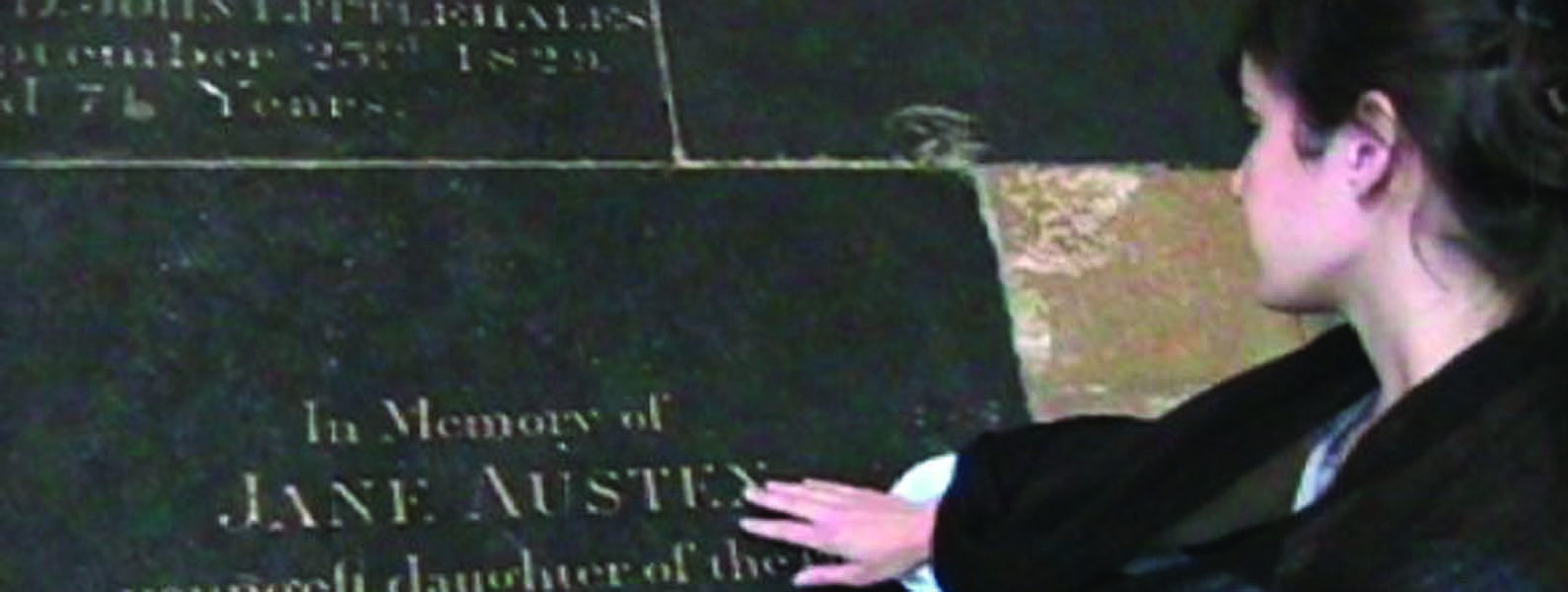

What makes Rzasa’s video project unique was that it was shot in many of the places where Austen lived in England. With the aid of a research award from UMBC’s Office of Undergraduate Education, Rzasa went to England to shoot her video at locations closely associated with Austen in Hampshire, including Chawton House (which is now a museum dedicated to Austen) and in Winchester Cathedral, where Austen is buried.

Rzasa says that officials at all of the locations were almost instantly obliging with permission to perform in these spaces. The bigger problems were the shortness of the time that she had to actually shoot the piece (less than a week) and creating a piece for spaces that were largely unfamiliar and had potential logistical constraints.

“I kept a lot of it as simple gestures,” Rzasa told the URCAD audience in a question-and-answer session after the video screening. “And I did test runs of the choreography.”

She was joined in performing the 20-minute-long piece by Elena Consoli ’07, dance, who lived in England and undertook graduate study at the University of Southampton when Rzasa made her video.

As Rzasa and Consoli romp through the meadows outside a parish church, or giggle together in pews, the viewer obtains a sense of the playful sensibility beneath the sense of Austen’s work. And as Rzasa literally dances tenderly on Austen’s grave in Winchester Cathedral, the project also conveys the tragedy of the author’s life cut painfully short.

Rzasa observed that the purpose of the piece was to use dance and Austen’s own words to cut through the fictions that have surrounded Austen’s biography and work. “The life and novels of Jane Austen have found frequent portrayal through film adaptations and television programs, but have rarely been depicted through a predominately dance medium,” she wrote in an abstract of the work.” The use of letters, she added, “sought to portray Jane Austen’s life without the biographical falsifications or embellishments noticeable in recent film productions concerning her.”

For more information about Undergraduate Research and Creative Achievement Day, visit www.umbc.edu/undergrad_ed/research/urcad/.

Oriole Observer

The appeal of studying orioles is obvious: They are arrestingly beautiful and easy to find in the Mid-Atlantic region – even on UMBC’s campus. The eye is easily caught by the contrast between the Baltimore oriole’s brilliant orange belly and its black head and wings. The state bird’s song is nearly as striking: a clear, loud, undulating whistle.

But Kevin E. Omland, an associate professor of biological sciences at UMBC, insists that the visuals are not what have drawn him to study these startling birds. It’s their evolutionary history.

Over the course of five million years, he explains, a single ancestral species gave rise to some 30 different species, most of which live in Central and South America. “We are using orioles as a model group to understand evolution,” he says.

Omland has used the DNA of the birds to work out a detailed family tree. From its branches, he can tell which birds are most closely related to each other, and, more importantly, begin to work out when various traits evolved and why. For instance, DNA evidence suggests that the birds had their origins in Mexico.

The family tree also led Omland to realize that Maryland’s orioles are “pretty strange.” Most of the rest of the oriole species do not migrate. And in many, if not most, of the other species, female birds are brightly colored and sing fluently, just like males.

“Some of the females sing more than males!” he exclaims.

The assumption that male birds are the ones that sing and wear showy plumage has led many scientists to ask the wrong questions about evolution, Omland says. Instead of asking how and why males evolved to be gaudy and musical, he argues, it makes more sense to ask how and why females evolved to be drab and mute.

For orioles, ancestral males and females probably looked and acted similar, shooting like orange-and-black balls of fire among the trees of Mexico, singing to each other.

Today, the description fits many tropical orioles – but not the Baltimore oriole or orchard oriole. Compared to the males, the females sing a simpler tune and look like a drab cousin, with a dull orangey-tan or yellow breast and olive-brown head and wings.

Why did the females lose their color and song? Perhaps predation targets females during migration or at the nest, and so they have adapted by blending in with their surroundings. Omland does know that over time, female orioles lost their bright color and song more than once – Baltimore and orchard orioles independently evolved these adaptations.

Omland has been studying orioles for 13 years to learn about evolution, and has no intention to stop: “We’re looking back in time. Sure, the view is fuzzy. You’re really squinting to see anything. That you can look back in time at all is so cool.”

For more information, visit www.umbc.edu/biosci/Faculty/OmlandLabWebpage/NewPages/.

Leading the Way

UMBC recently filled two key academic leadership posts with faces who have become quite familiar on campus.

• Janet Rutledge has been tapped as Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School, leading the university’s efforts in graduate education. After taking her undergraduate degree at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and her doctorate in electrical engineering at Georgia Tech, Rutledge taught at Northwestern University and worked at the National Science Foundation. She has held numerous leadership positions in UMBC’s Graduate School, including Acting Dean of the Graduate School and Interim Vice Provost before assuming the position permanently.

• The university has selected Geoff Summers as its new Vice President for Research, leading UMBC’s efforts to advance research and creative activity. Before arriving at UMBC, Summers took undergraduate and graduate degrees (including a Ph.D. in physics) at the University of Oxford, and he taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Oklahoma State University. At UMBC, he has served as the chair of the Physics department and founding dean of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences.

Coming of Age

For a U.S. population that is living longer and healthier, the Erickson School at UMBC is “the right school with the right topic in the right location,” says Erickson School professor Joseph Gribbin.

The school’s emphasis on combining the study of aging itself with courses on management and public policy means that its 341 students in graduate and undergraduate programs are receiving a unique multidisciplinary education that is a model for other U.S. colleges and universities.

“Aging isn’t a bubble,” says Judah Ronch, who was recently named interim dean of the Erickson School. “This program requires multiple perspectives and collaboration. Students enrolled in our courses don’t have to major in the subject. It’s just about opening our eyes to major social issues.”

UMBC’s leadership position in aging studies was sparked by John Erickson, the founder and chairman of Erickson Retirement Communities. A donation of $5 million to the university from the eponymous foundation created by Erickson and his wife, Nancy, was the impetus for the school’s creation.

While the ailing economy has forced the Erickson School to be more conservative about its expenses (including layoffs and cutbacks earlier this year), student enrollment in its programs at all levels has been strong and growing.

The momentum makes Ronch confident in the school’s future success. “Our mission remains the same,” he says. “How to fulfill the mission will be modified. There will be changes in strategy, and we’ll be doing more with less.”

New courses in entrepreneurship, diversity, mental health and others are part of the change in strategy. This fall’s executive education offerings have been re-tooled to appeal to a broader market – from junior management to upper level executives. For example, the school’s most popular executive education offering, Business and Finance, will address immediate economic realities in the seniors housing and care markets.

Increasing use of online resources is another innovation. Courses such as an online version of Aging 100 will be an option for fall 2009, and Aging 200 and Aging 300 will be online by spring 2010.

These strategic changes and others – graduate courses are now eligible for financial aid –were spurred not only by student feedback, but by simple demographics. A majority of the school’s students come from nontraditional backgrounds, and have personal obligations such as family care. The changes will allow greater flexibility in earning a degree.

Another nontraditional key for growth at the Erickson School is its use of social media as a recruiting tool, weaving blogs and video into more traditional media outreach.

“Our blog, ChangingAging.org, gives us a global presence and uses a variety of multimedia,” says Bill Thomas, a professor at the school. “It’s driven by what we think is going on and how it’s going to play out.”

The Erickson School is already counting successes among its high-profile alumni.

“Collectively, we’ve had mostly high-level executives as part of our program,” said Gribbin. “Those executives have rebuilt plans for their companies as a test of their degrees. That’s validation right there.”

The school’s new leadership is ready to capitalize on that success and the power of the nation’s changing demographics. Aging studies presents “the greatest opportunity of the century,” says Thomas. “I foresee a day when UMBC is known for [aging studies] like it is for science, engineering and technology.”

Practically Minded

Uri Tasch, a soft-spoken Israeli-born mechanical engineer, has always had an eye for the practical. First, it led Tasch – a professor of mechanical engineering in UMBC’s College of Engineering and Information Technology – to develop a device for detecting lameness in dairy cows.

And over the past five years, Tasch has developed a variation of that same veterinary device that may be useful for human medicine – including the early diagnosis of neurodegenerative conditions like Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), popularly known as “Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

Time spent every summer on his uncle’s kibbutz led Tasch to want to develop a “smart” system to automate milking and provide feedback to farmers about each animal’s productivity. But after graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering in the early 1980s, he discovered that the automated milking field was highly competitive.

So Tasch browsed the agriculture journals looking for other ideas. Eventually, he stumbled across a paper describing the problem of lame cows – a dilemma that, at the time, cost the U.S. dairy industry about $600 million annually. Many factors can cause lameness in cows, including injury, arthritis and infection, but diagnosing the problem at an early stage is difficult and laborious.

Intrigued by the problem, Tasch invented a device to automate the diagnostic process. It measures three characteristics of each animal’s gait: the body-weight distribution, the foot placement, and the vibrations generated as each foot strikes the platform. If an animal is experiencing pain in one leg, it typically puts less pressure on that limb. The lame or injured limb strikes the floor more gently and generates fewer vibrations in the device.

Tasch developed software that creates a single number denoting the probability that the animal is lame and even identifies the limb needing treatment. The device was granted a patent in 2004 and marketed as The StepMetrix TM.

Along with a similar device for horses, Tasch also developed a variation of the machine for rats to test the device’s application in a new arena: diagnosis of progressive degenerative neuromuscular diseases like ALS in rats that have been genetically engineered to develop the condition.

“ALS, Parkinson’s Disease, Huntington’s are all neurodegenerative diseases that affect the way you move,” explains Tasch. He is betting that analyzing the forces generated by an animal as it moves across the platform may yield clues to a diagnosis.

In back-to-back publications within the last six months, Tasch has shown that his device can identify rats that are genetically programmed to get ALS with 98 percent sensitivity. Tasch receives his rats when they are just 28 days old.

“At 120 days these rats will be dragging one foot or not using it,” says Tasch. “We can detect ALS at about 50 days.”

Before Tasch can get approval to build a device for humans, he must prove that the device can accurately detect disease by testing it on a much larger group of animals.

“The earlier we can detect these diseases, the more time we have to experiment with drugs and see which ones are effective. It’s a race.”

Tags: Fall 2009