As election season heats up and campaign posters begin to cram our sidewalks, the public eye is often drawn to government leaders. In UMBC’s own community, you’ll find alumni serving in impressive positions, including state legislators and the speaker of Maryland’s House of Delegates, a county executive, and even the surgeon general of the U.S.

But beyond the red, white, and blue banners are folks who contribute to the system in quieter—but just as vital—ways. Students learning to be engaged citizens, professionals protecting our census and voting data, artists finding ways of illustrating complex ideas, and more—Retrievers are proving that when it comes to democracy, every voice really does count.

Peek Behind the Scenes

Most of the work at all levels of government happens beyond public view. Matt Clark ’00, history, and Yaakov “Jake” Weissmann ’06, social work, know this firsthand. Clark served as chief of staff to Maryland Governor Larry Hogan while Weissmann is chief of staff to Maryland Senate President Bill Ferguson.

Both agree that the behind-the-scenes nature of their roles helps them get things done. Clark explains that “if you are doing it right, politics and public policy are all about compromise and patience” and that you need to “build coalitions and trust with others to move your agenda forward.” Weissmann emphasizes the importance of relationships, noting that his social work major has aided his work in Annapolis.

Public service is “at its core a people business,” Weissmann says. Jim Bembry, associate professor of social work, taught him that: “You need to be where your clients are”—words he says help him understand what senators and their constituents need and how to help fill those needs.

Clark says his undergraduate history studies taught him “how to blend multiple points of view to construct your own ideas and perspectives,” a helpful skill for both the political and public policy aspects of his job. Clark adds that his ongoing public policy graduate studies at UMBC “help [him] to think about how theoretical concepts and actual policy-making interact.”

Clark explains that “not all public service [jobs involve] politics,” but rather “public service is about choosing to look beyond your own needs to serve your community.” Weissmann agrees, noting that the General Assembly consists of people “who all want to make a difference,” he says, and Maryland’s legislature is an example of “how government is supposed to function.”

UMBC is well-represented in Annapolis, and both Clark and Weissmann interact with fellow alumni—including each other—on a regular basis. Clark attributes the prevalence of Retrievers in public service as “a testament to the quality of the University as well as the values and grittiness that we pick up there.” Weissmann agrees, sharing “UMBC is where I fell in love with the General Assembly” as part of a student group that met with legislators about and testified against proposed tuition increases.

Clark advises fellow Retrievers who want to pursue a career in public services to “put your heart into the work and believe in what you are doing,” noting that “it can take years to see the fruits of your labor, but it’s well worth the wait.”

— Mary Ann Richmond ’93

Predictive Polling

As the November elections draw near, we are flooded with polls anxious to tally how we will vote. But, have you ever wondered about the science behind these polls? Designing surveys to help understand American voting behavior is what gets Ian Anson out of bed and excited for the day.

During the 2018 midterm primaries, Anson, a professor of political science, saw an opportunity for his voting and polling class. Thus the 2018 UMBC Retriever Exit Poll was created.

“I wanted to expose my students to the real-life experience of tapping into the mind of the public and figuring out what the public thinks, and how they react to political stimuli,” says Anson.

The class created a 34-question, voluntary, anonymous, and scientific exit poll. Questions covered the Maryland economy, voting behavior along party lines, the state income tax, and switching party lines for specific items. On a rainy mid-term Election Day, 25 undergraduate students, wearing UMBC Political Science T-shirts, stationed themselves in eight precincts across Baltimore County in four-hour shifts. They organized and coded the answers on-site.

At the end of the day, Anson processed the data. Everyone gathered at UMBC’s Election Night Extravaganza where they presented their data and correctly predicted Governor Hogan would be reelected. The students gained insight into the voting behavior of Maryland Democrats who voted for a Republican governor and the issues that concerned them.

“We left the bubble of campus to see how real voters act and think instead of just reading and writing about them,” says Samuel Deschenaux ’20, political science, now a legislative aide in the Maryland General Assembly for state Sen. Kathy Klausmeier. Anson looks forward to the next Retriever Exit Poll this fall.

— Catalina Sofia Dansberger Duque

Outsmarting the Hackers

During election years, if there’s one thing scrutinized more than the candidates themselves, it’s the security of electronic voting machines. Because this technology can be susceptible to hacks and other vulnerabilities, it is incredibly important to know how best to keep voting safe and accessible for all.

Enter Rick Carback ’05, M.S. ’08, Ph.D. ’10, computer science, who has spent his career deflecting would-be hackers, and who helped develop Scantegrity, a technology that since 2007 has influenced improvements to election systems nationwide. At UMBC, he worked alongside and was mentored by Alan Sherman, professor of computer science and electrical engineering.

As an undergraduate at UMBC, Carback first heard David Chaum, a cryptographer known for his work on privacy-centered technology, talk about the security of voting machines and the voting technology that he was working on. Carback approached Chaum after the event and expressed his interest in being involved with the building of the technology that Chaum had discussed. From there, a lifelong interest in security took off.

First tested with student elections at the University of Ottawa and later broadened to handle higher stakes cases, Scantegrity connects each submitted vote with a confirmation number so that people can make sure their votes were counted. It helps verify election ballots submitted and allows individuals to essentially audit the election— while protecting individuals’ data.

Carback’s work also takes accessibility into account. The initial version of Scantegrity included ballot marking systems, which can make voting easier for people with disabilities. The ballot marking system used invisible ink that would not show up outside the official voting space on the ballots. With this system, the machine would only count a vote based on where the ink is most dense on the ballot, Carback explains.

“I view [voting security] as a national security issue,” says Carbeck, who also does computer security, risk assessment, and software development from Boston. “If you can control an election, you can then you can direct the entire course of a country.”

— Megan Hanks Mastrola

Stories Are Everything

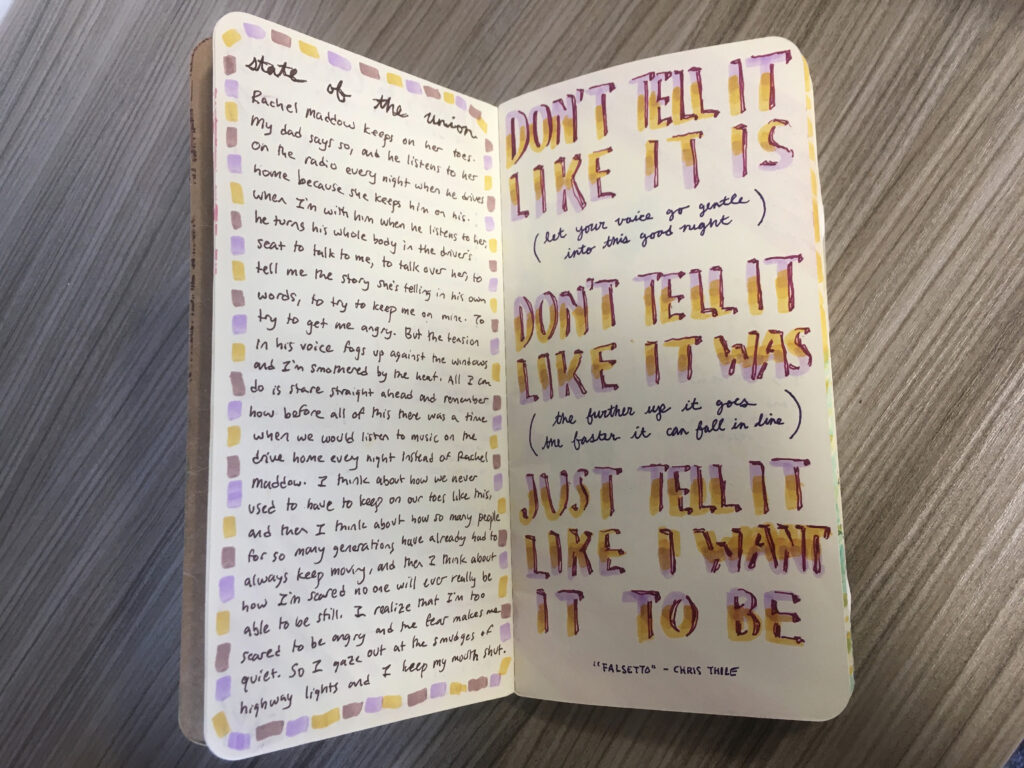

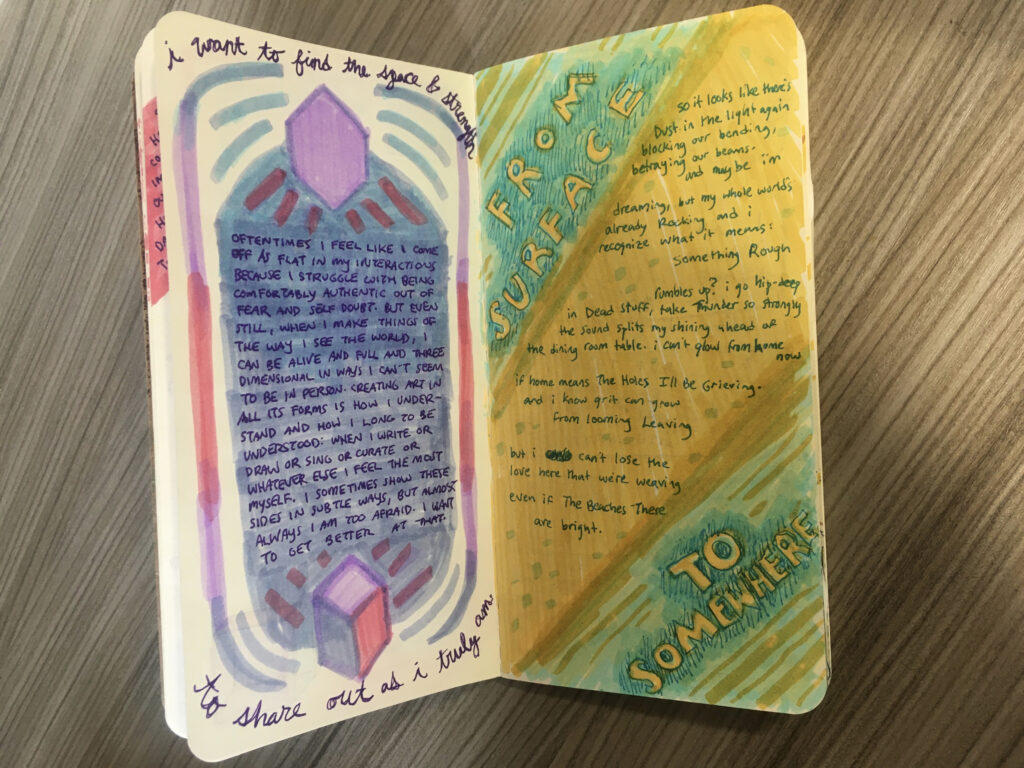

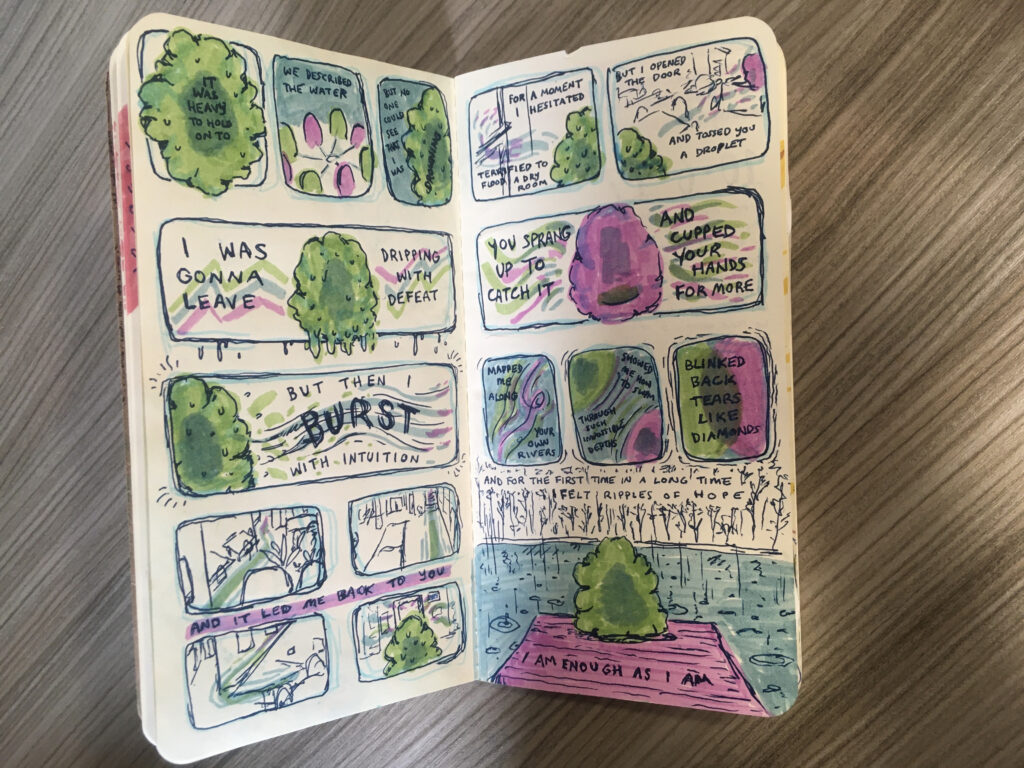

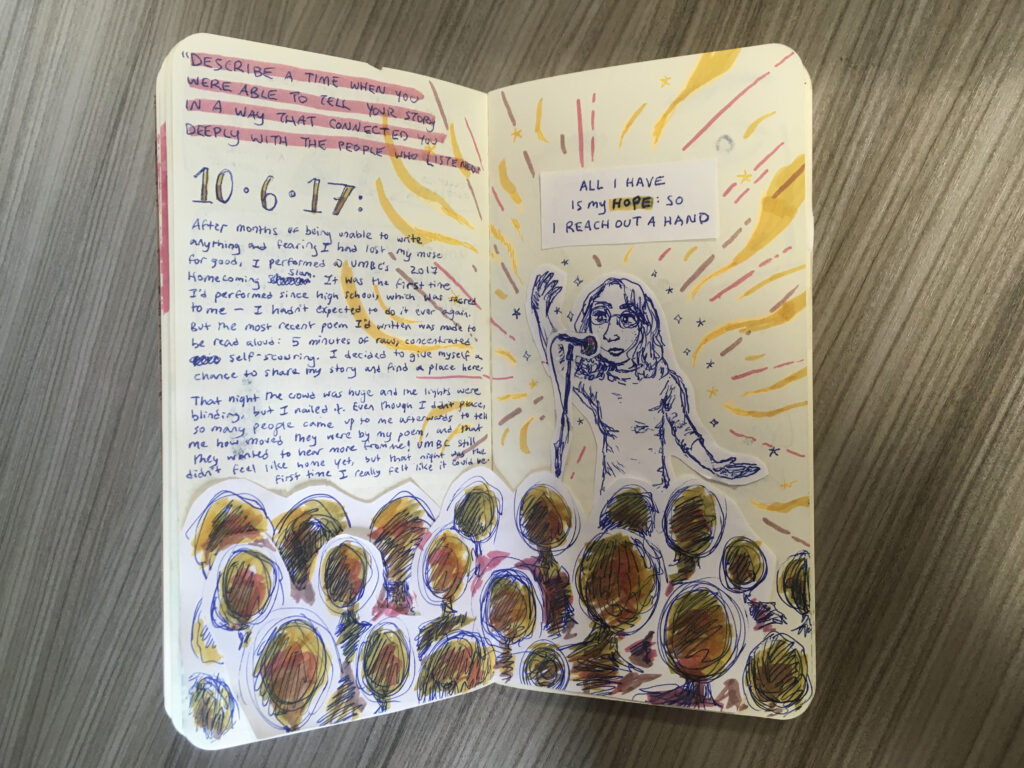

In grade school, we learn about the importance of voting. At UMBC, we learn that civic life can really mean much more. It is a mindset, strengthened by places and relationships, to empower change at big and small levels. And the Civic Courage Journaling Project, launched last year by UMBC’s Center for Democracy and Civic Life, is helping students imagine exactly what that might mean on an individual basis.

“We give them a way to really see themselves without all of the kind of filters that are placed on you when you’re under so much pressure and when you have all these different tensions,” says Tess McRae, a junior English major who both participates and shares prompts with the group. Members respond in visuals as well as with words. Then, they all circle up to discuss and discover.

“People don’t realize that we talk about civic life everywhere, even in our day-to-day interactions, even in the conversations that we have with each other, even in spaces where we didn’t realize,” says McRae, who personally prefers using muted highlighters in her drawings. “We kind of give people a space to just really be authentic and honorable about their stories. It’s wonderful.”

— Jenny O’Grady

Safety in Numbers

Every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau conducts a massive survey to answer one question: Who lives in the United States? The results inform federal funding allocations for things like schools and parks and determine the number of congressional representatives for each state. The raw data are also used by researchers all over the country, whose findings can inform decisions at the state and local level about medical services, urban planning, job training programs, and so much more.

Analyzing all that data—consisting largely of personal information about members of communities across the U.S.—can lead to a lot of good, so it’s important that researchers can access it. But even with obvious identifying information like names, addresses, and social security numbers removed, it still wouldn’t be hard for skilled hackers to identify some people using the remaining information, putting them at high risk for identity theft. That’s why Bimal Sinha, professor of mathematics and statistics at UMBC, has been working with the Center for Statistical Research and Methodology at the U.S. Census Bureau for the last seven years to help safeguard people’s information.

It turns out the “raw data” the Census Bureau delivers to researchers doesn’t exactly match the real data. “Before releasing the data, some sensitive items are changed,” Sinha explains. That can include numeric responses, such as salary, or categorical ones, like whether a person owns a car and what type. The process of changing the data is called perturbation,” and the techniques used depend on the kind of data.

The tricky part is that the “perturbed” version of the data still has to accurately reflect reality in the country. Change it too much or in the wrong ways, and it becomes useless. “It’s a balance between perturbation and utility,” Sinha says. As a statistician, it’s Sinha’s job to develop techniques to change the data in ways that protect people’s privacy but don’t render it unusable.

Once that’s been done, it’s also critical to help researchers analyze the data effectively. The method for analyzing a perturbed dataset is different than for a standard data set. So Sinha also helps develop a toolkit that researchers receive with the census data.

Overall, Sinha’s work allows researchers, state and local governments, non-profits, and others nationwide to make use of the largest dataset about humanity in the United States, without compromising people’s privacy or safety.

— Sarah Hansen, M.S. ’15

Walking the Walk

We all know the importance of getting an internship—real-world experience, networking opportunities, a chance to confirm you’re on the right career path. For these UMBC students, it was also the opportunity to see the inner workings of the political realm as they embarked on semester-long internships with Maryland delegates.

You might think a legislative internship would be all work and no play, but that’s not always the case. One day when Wangui Nganga ’22, global studies, was answering phones in Del. Mike Griffith’s office, she got a bit of a surprise on the other end of the line.

“I heard ‘hello’…and they proceeded to tell me a joke and hung up,” she remembers. “I told my coworker I thought I was prank called by a constituent, but she started laughing and said it was her. This was one of my favorite moments because it showed that people don’t take everything super seriously.”

Nganga’s involvement as a research assistant for a professor in UMBC’s School of Public Policy and speaker of UMBC’s Student Government Association prepared her to do the research necessary to succeed in her internship. The environment itself is welcoming and understands that the purpose of everyone’s work, regardless of political affiliation, is to improve the lives of Marylanders.

Through the Maryland General Assembly Internship Program, Matthew Harrington ’20, political science, had the chance to explore his passions even further.

“I chose to work for Del. Julie Palakovich Carr because she sits on the Ways and Means Committee, which deals with tax policy, which is my policy area of interest,” says Harrington.

In his short time there, Harrington had the opportunity to present a bill about reforming zone programs in the Ways and Means Committee on behalf of his delegate. In addition to the numerous hands-on ways he’s able to be part of the process, Harrington also notes that the free food at Annapolis receptions doesn’t hurt either.

— Kait McCaffrey

Seeing Is Believing

Many of us have trouble digesting straight numbers. And for every hour a journalist might put into clearly explaining a complex topic in a story, an accompanying image can either support or derail that work for the reader in a matter of seconds.

That’s where Christina Animashaun ’13, visual arts and media and communication studies, comes in. As a data journalist for places like Vox, and formerly Politico and The Washington Post, she marries art and data to make the big numbers tangible.

It often starts with a simple question, says Animashaun, who grew up watching the evening news and reading comics before coming to UMBC as a Linehan Artist Scholar.

“A lot of times we have a lot of ideas, and in order to turn them into something tangible—art, or an article—you really have to be able to hone in one question. One big idea.” In the case of a recent major news topic like coronavirus, for example, that might mean drilling through dozens of numbers to help quantify a question like “What do I need to be safe?” Animashaun has made some equally beautiful and scary coronavirus charts recently but also loves to layer archival photographs in fun and surprising ways.

Of course, with great power comes great responsibility. Because Animashaun understands just how much a color or shape choice can sway opinions, she does everything she can to stay as neutral and accurate as possible and bring an ethical point of view to her work.

“You’re not going to see any pinks from me,” she says. “And if it’s blue, it’s going to be a partisan blue.”

— Jenny O’Grady

*****

Illustrations by Christina Animashaun ’13.

Tags: PoliSci, Spring 2020, UMBCTogether