Some classes translate better to remote learning than others. There was no way for students in Adam Mendelson’s advanced lighting design class to emulate the experience of programming and running massive lighting rigs from their homes. But, as it turns out, there are lessons about lighting design to be learned even in one’s own bedroom.

Mendelson, a senior lecturer in the Theatre Department, and his students discovered this after one of their projects—design lights to accompany a reading of a poem—had to be transferred to online. Students were given the option to complete the project using online simulation software or take a hands-on approach by using the lights sources available in their house.

The DIY students used whatever materials they had on hand, from Christmas lights to flashlights to simply opening or closing the blinds of a window. About half of the class went this route, enlisting the help of family members and housemates to flip switches or plug lights in on cue, one even used their dog as a lighting model.

This experimental assignment has proven successful; Mendelson was pleased with the creativity and innovation his students have shown. “One person used three or four different desk lamps that they put different colored light bulbs in,” he says. Another student used t-shirts and papers to change the colors of flashlights. “He took apart a shoebox and he put five chess pieces in it and that was the surface he was lighting,” Mendselson says. “It was really beautiful.”

“As a lighting designer for a theatrical or a live event, every single thing that lights up is in your purview,” says Mendelson as a takeaway from the at-home version of this assignment. “Sometimes it’s something you can control and sometimes it’s not,” he explains, using green “exit” signs in a space as an example of something that the lighting designer might have to account for. “The key to lighting design is controlling the light and putting the light where you want it to go.”

Other assignments have been more challenging to translate to a distance-learning format; traditionally, students in the class have the opportunity to light a live dance performance, but those shows were canceled. Nothing can replace that live experience, says Mendelson. “That objective of being in the room and having to make quick decisions and all of that is practically impossible to recreate.” Instead, he is asking students to attend a supplemental webinar or online class to help fill in the knowledge gaps left behind by the sudden pivot to online learning.

Testing the Waters

Suzanne Braunschweig, a senior lecturer in the department of Geography and Environmental Systems and director of the Interdisciplinary Science Program, has also faced the challenge of transferring hands-on lessons into a digital space. Science 100: Water, An Interdisciplinary Study, the GEP lab science course she teaches, usually involves traveling to the creeks and streams on campus to collect data, but, because of the dangers of COVID-19, many students can no longer even go into their backyards to collect data.

The solution, Braunschweig has found, is to give her students virtual lab assignments that mirror the course’s in-person labs as closely as possible. One assignment, for instance, typically involves going to a nearby stream to find and identify benthic macroinvertebrates—small organisms that live in the bottoms of lakes and streams. In the virtual lab, students will still go through the same steps of identification that they would in person, albeit using high-quality photographs rather than real organisms.

According to Braunschweig, the analysis aspect of the lab will also be essentially the same as it would be in a traditional classroom setting: “Based on the assemblage of critters that you find, you can then make conclusions about the quality of the stream from which they would’ve come.” Usually, she notes, students are excited to find that the streams on campus are “in good shape.”

Transitioning to running online labs has been far from a solo project—Braunschweig’s colleague Susan Schreier and several teaching assistants have assisted with finding virtual materials and making sure the labs run smoothly. She has also utilized a number of invaluable online resources, such as data collected by local nonprofit Blue Water Baltimore.

As part of its mission to restore the quality of Baltimore’s waterways, Blue Water Baltimore maintains a database of information about the health of Baltimore’s rivers and streams. This data has proven to be a “godsend,” says Braunschweig, replacing data students would have sampled from streams around the Baltimore area.

“It’s not doing hands-on work, but they still have the ability to analyze data, and put things in context for the greater Baltimore area in terms of water quality,” Braunschweig says.

Braunschweig knows that most of her students take Science 100 to fulfill a general education requirement, but she’s found that they are still giving their all, even remotely.

“They show up, they stick around, they actually try to work through the lab material during their lab time,” Braunschweig says. “I really admire them for sticking to that because it’s hard, under the current circumstances.”

Lending a (Virtual) Hand

While instructors of hands-on courses knew from the start how difficult this pivot would be, Kate Drabinski, lecturer of Gender, Women’s, + Sexuality Studies, never could have anticipated how much she still had to learn about online teaching. After all, she had years of experience with teaching online and hybrid courses, and had even signed up to help train her fellow professors how to use various distance learning technologies.

But the technical side of things didn’t turn out to be the biggest challenge for faculty to navigate, Drabinski says. “The faculty I worked with needed to know that what they were planning to do was a good idea and would work,” she explains. “They needed to hear that we could do this, that we were all unsure of what our new classrooms would look like, and that we would be able to find strategies that would work to keep us and our students moving forward in a time of great uncertainty.”

For Drabinski’s own classes, the strategy has been to decrease the amount of work students have to complete. “We don’t all have equal access to technology, workspaces, time, or other resources to learn best, and my workload has to respect those differences,” she says. She also knows that it can be difficult for students to give schoolwork their full attention when they are contending with the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as losing their jobs or having to take care of sick family members.

She has also opted to use a synchronous learning approach paired with recorded lectures. That way, she meets with her students in Blackboard Collaborate during her regularly scheduled class times but each student can decide whether they prefer to come to class or watch the video later.

“This approach builds structure for those who need it while recognizing that others have different needs,” Drabinski explains.

Continuing Connections

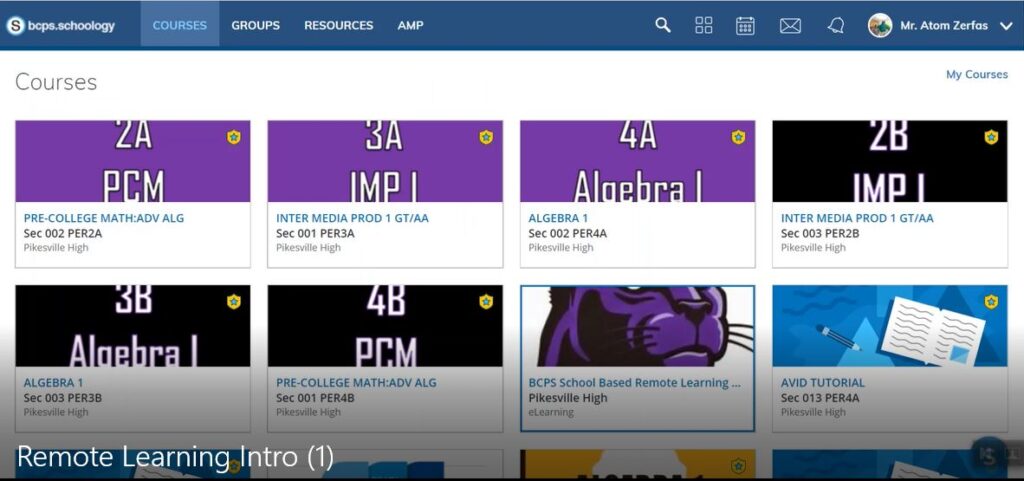

UMBC professors aren’t the only ones leading the charge into remote learning. Atom Zerfas ’13, mathematics, M.A., ’14, education and teaching, a math teacher at Pikesville High School, played a pivotal role in introducing the students at PHS to how the final quarter of the school year would play out. He created a video to help guide students through what their new class schedule would look like, how they would access online materials, and how they would get in contact with their instructors.

He decided to make the video after seeing how stressful the transfer to remote learning was on the teachers’ end. “It was extremely overwhelming for us, functioning adults who are supposed to be able to ‘be the calm’ for our students,” he explains. “I couldn’t imagine what it would have been like to be a student in any grade, wondering what this means for them. I wanted to provide as many answers that I could, as soon as I could.”

Zerfas originally made the three-and-a-half minute video for the students in his classes, but then restructured it so that the entire school could use it as a resource. Later, he found out that teachers at other high schools were using his video, despite it being tailored to how PHS, specifically, was restructuring its curriculum.

Online teaching isn’t entirely new to Zerfas. He has been uploading recorded lectures for a few years now in an effort to support students who missed class or just need a refresher on the material. The videos he is making now, however, have a purpose beyond education; he wants them to be a beacon for his students.

Video lectures give Zerfas the chance to say “Hi,” he says, and “let my students know that I’m thinking about them, and show them that I’m here if they need me for anything. I know a number of other teachers are dressing up, wearing wigs, or trying to make it as fun as they can. It really comes down to use trying to reconnect with our students, support them, and restore a sense of normalcy and joy.”

In addition to keeping in contact with his students, Zerfas has also been making sure to maintain another important connection these past few weeks: “I’m lucky to have been part of UMBC’s Sherman program because I’ve been connecting with a lot of my cohort members recently, and we’ve just been checking in with each other and being as supportive as we can.”

Making Permanent Change

Though distance learning will not always be necessary, instructors at UMBC and beyond are proving that they are capable of delivering online lessons that are compelling, stimulating, and sometimes even fun for students. Perhaps this unusual semester will give way to lasting, innovative teaching practices, from providing recorded lectures to maintaining more open lines of communication between professors and students.

Ultimately, though, the biggest takeaway lies not in any particular teaching strategy or technological tool. Rather, what we all must learn from this pandemic is that the UMBC community is strong enough to overcome great adversity—but only when we are able to be patient and understanding of each other’s unique challenges and circumstances.

“Not all students have the ability to study or do their [homework] in peace. It’s just more noticeable now,” Zerfas says. “That doesn’t mean to stop offering resources or to stop pushing your kids to do more, but to differentiate lessons more and not to penalize the kids who couldn’t do it.”

*****

Header image: Pig Pen Pond, a common Science 100 site, sits between campus and bwtech@UMBC.

Tags: COVIDresearch, professorsnottomiss, Spring 2020, UMBCTogether