UMBC professor of political science Thomas Schaller’s 2006 book Whistling Past Dixie offered a controversial roadmap for the Democratic Party’s path back to electoral success – and thrust him into the D.C. spotlight. What does he see ahead in an already fractious 2012 electoral cycle?

UMBC professor of political science Thomas Schaller’s 2006 book Whistling Past Dixie offered a controversial roadmap for the Democratic Party’s path back to electoral success – and thrust him into the D.C. spotlight. What does he see ahead in an already fractious 2012 electoral cycle?

By Richard Byrne ’86

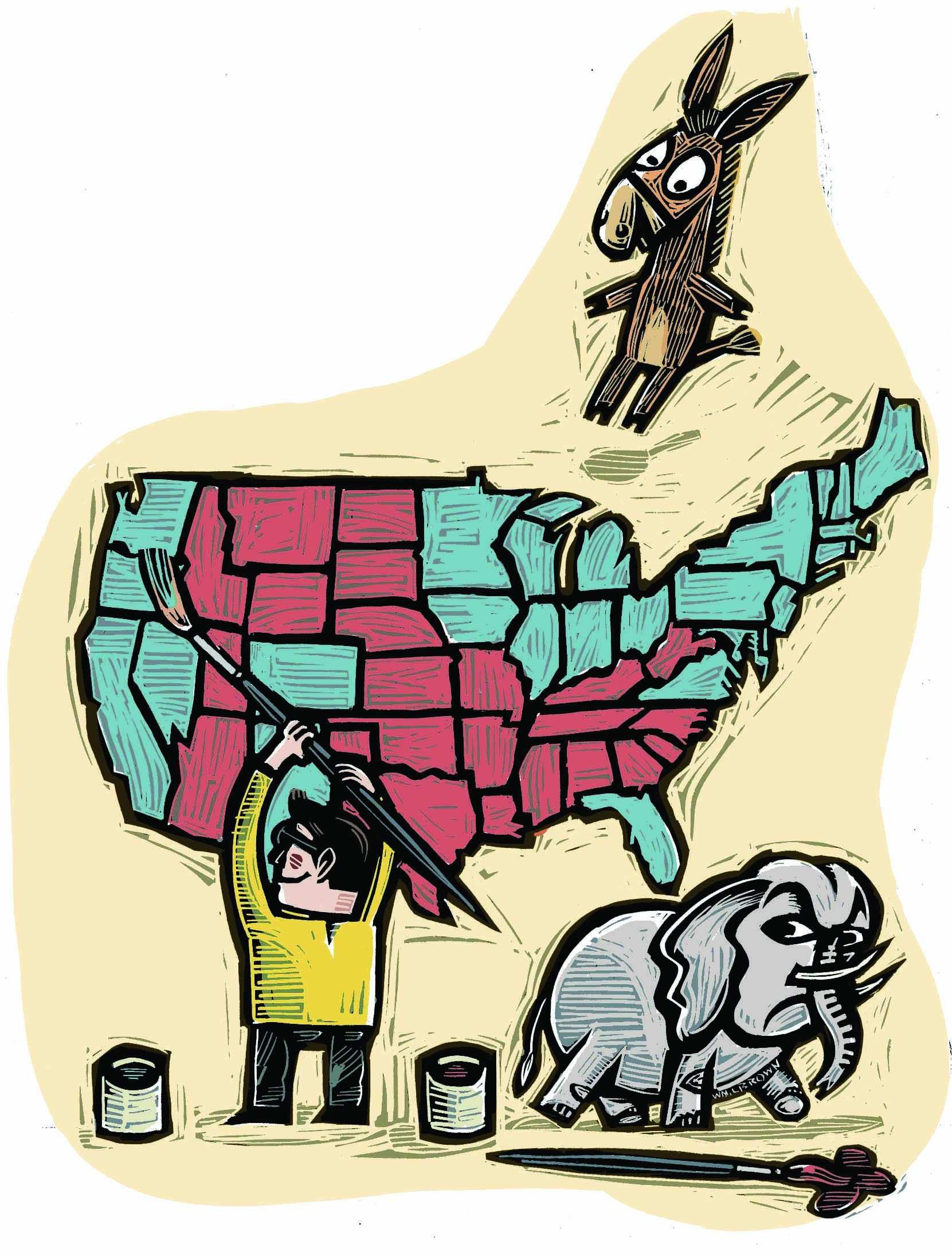

Illustrations by William L. Brown

Professor of political science Thomas Schaller is an affable and loquacious fellow – a consistent pick among UMBC undergraduates as one of the university’s top teachers, as well as a fan of the rock band Wilco and the Washington Capitals hockey team. But Schaller has attracted as much (if not more) attention off-campus as one of the national media’s go-to sources for commentary on America’s polarized politics and as author of the 2006 book Whistling Past Dixie (Simon & Schuster).

The premise of Whistling Past Dixie was breathtaking. Schaller combed through electoral history and crunched the numbers to fashion an argument that the path to reinvigorating the Democratic Party’s moribund electoral prospects lay in shifting attention from increasingly failed attempts to win over the culturally conservative and racially polarized voters of America’s Deep South (South Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia). He proposed that Democrats forge a new coalition stretching north from the party’s strongholds in the Northeast across the Midwest and Southwest and then along the nation’s Pacific Coast.

The argumentation – and the writing – in Whistling Past Dixie were sharp and witty. “Rather than trying to compete in Alabama,” Schaller quipped, “the [Democratic] party should first figure out how to convert Arizona, or even Alaska.” But the book’s crackling attack on the South as the “electoral graveyard” of the Democratic Party also elicited controversy and pushback.

On the website Salon, for instance, Democratic pundit and strategist Ed Kilgore dubbed Schaller’s recipe for success as a “run against the South prescription,” and warned that “the idea that Democrats will do well by attacking Southern culture is just plain dangerous.” At the end of the day, however, Schaller’s arguments triumphed where it counted most – at the ballot box. In both 2006 and 2008, the U.S. electoral map was very blue in the places where Schaller urged Democrats to focus – and remained quite red in the Dixie that he urged the party to whistle past.

Predicting this recipe for electoral success has made Schaller a force in the analysis of America’s political scene in newspapers (The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Baltimore Sun, The Guardian), in magazines (The New Republic, The American Prospect, Salon) and in appearances on local and national television and radio.

In many ways, Schaller has been able to marry his early training in communications to his training as a political scientist. He took a B.A. in the former from SUNY-Oswego, before studying political science at Florida State University (M.S.) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Ph.D.). He also co-authored a book, Devolution and Black State Legislators: Challenges and Choices in the Twenty-First Century, with UMBC colleague Tyson King-Meadows, an associate professor of political science.

UMBC Magazine caught up with Schaller to talk about the American politics of the recent past, present and future as the nation enters another fractious political season.

Q: As a political scientist, what effect does America’s election cycle have on your research?

A: Elections come around every two years for Congress and every four years for the presidency. And the United States has been around for a long time. So you can actually generalize about American presidential and congressional elections. We’ve had them without fail for more than two centuries. Compare that, say, with some of the democracies that arose out of the Second World War, which have only been electing public officials for 60 years or so. So it’s nice to have a rich, deep set of data that’s being updated every other or every fourth November.

You can do the same with budgets or Congressional roll calls. Some political scientists have looked at roll calls going back to the very first Congress in 1789. That’s just remarkable. It’s the blessing of having a long and stable democracy, whatever its failings or faults, and regular uninterrupted elections without coups or takeovers or generals usurping the power of a government and banning or barring elections for a decade or two.

Q: What first excited you about political science?

Q: What first excited you about political science?

A: I always struggled in graduate school with what many graduate students struggle with: How is what I’m doing meaningful? How is it relevant? How is it exciting? Those questions made me gravitate toward American politics. Contemporary politics, more specifically. And, even more specifically, practical politics. I always felt that criticism that political science was becoming increasingly disconnected from practical politics was real. There was a famous article written by Jonathan Cohn in The New Republic in the late 1990s called “Irrational Exuberance” that essentially said: “Political scientists used to advise presidents, governors and other politicians. Now they’re devising complex models and discussing them on a panel with 12 people in the audience at a political science conference. It’s become a navel-gazing science at a time when it should be even more relevant to practical politics and policy.”

I was always one of those people who felt that disconnect, and wanted to be a political scientist who was following current events and writing and reading and thinking about them.

Q: Was there a light bulb moment for Whistling Past Dixie?

A: I was at a wedding in Berkeley sometime after the 2000 election. A friend of mine, Jim Cox, who also got his Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina and teaches at Cal State Sacramento, was getting married. And I’m standing at the bar during the cocktail hour and saw Jon Gordon, with whom I also went to graduate school. And at that time, I was as much a victim (if you will) as everyone else of the conventional wisdom of that time, which was that Democrats needed to get back to reaching working class white voters – and especially Southern white voters – and that if they didn’t they would be a minority party in perpetuity. And Jon said to me: Why? And I didn’t have an answer, other than everybody said so. The Democratic leadership. The [pollster] Stan Greenbergs of the world. The [political consultant] James Carvilles. The people who had elected [President Bill] Clinton. So they must be right.

But it had been almost 10 years since that election and the country had changed. So I just started from scratch. Looking at the numbers. How many electoral votes did Clinton get outside the South? Actually, he did get more than 270. So it had already been done. Then I looked at regional representation: congressional delegations, governors, state legislatures. And I started thinking: “Wow, this is so counter-conventional wisdom that it might be cheeky to argue it but it might be right. It might be possible and true.”

By fall 2003, I had written a piece that I was shopping around and getting a lot of doors closed in my face. But then I pitched it to Steve Luxenberg, who used to work at The Baltimore Sun and was at that time the deputy editor of the “Outlook” section of the Sunday Washington Post. He thought it was a brilliant piece and ran it on the front page of the “Outlook” section in mid-November. And then I started getting calls from people whose work I really respected – people like [political writer] Larry Sabato and [pollster] Charlie Cook. And I thought: It’s more than just a counterintuitive notion.

Then I went back and read what had been written 40 years ago by Kevin Phillips about how the GOP could win in the South. I realized the time had come for a non-Southern strategy and a non-Southern realignment of the Democratic Party.

Q: Whistling Past Dixie drew a lot of pushback from the Southern Democratic establishment.

A: Your audience when you write a book for Simon & Schuster is a lot different than when you’re writing for an academic press. A lot more people are paying attention. But the people who weren’t happy with the book basically fell into three categories. The punditocracy was one group. Then there were people in the field of Southern politics and political science. And the third group was practical people: party people and pollsters. And the biggest blowback came from the final group. It’s in their vested interest not to take a cold and clear-eyed look at the book.

Whistling Past Dixie is an argument in game theory, though I don’t use those terms in the book. Given scarce resources, where can you win? Well, if you look at the demography of the country these are the places that can give you the highest rate of return. It’s not an anti-South book. It’s a “where can you win?” book in the economy of partisan politics.

But it wasn’t shocking that people who make their living as experts on Southern politics like [political strategist] David “Mudcat” Saunders told me to “kiss their rebel ass.” Or Donnie Fowler Sr. – a longtime giant in South Carolina politics – whom I saw at a conference talking about me without him knowing I was there. He called me some unprintable names. You can understand how people feel it was a personal attack, but it wasn’t.

Q: People often see universities as “ivory towers,” but the book placed you squarely in the mudslinging of the political arena of politics.

Q: People often see universities as “ivory towers,” but the book placed you squarely in the mudslinging of the political arena of politics.

A: If I’m honest with myself, it was an itch that I wanted to scratch. When you feel like you have the right argument, you want to be heard and you can be heard in academic circles, and that’s important, but when you can move the national debate a little, you want to do that. The novelty and the thrill of it have worn off quite a bit, but it was something inside me and I needed to check that box off. You feel like you have to go up and ring the bell one time, and I did.

Q: Your argument in Whistling Past Dixie was validated in spectacular fashion when you look at the 2008 presidential electoral map. Obama’s winning coalition was precisely the one you laid out: Northeast and Pacific coast states, with big inroads in the Midwest and gains in the Southwest.

A: I’m even more proud of the 2006 electoral results. Eighty-five percent of the Democrats’ net pickup in seats was won outside the South in that cycle. This literally happened six weeks after the book went into print. Those gains were across the board and at all levels – top to bottom of the ballot.

Latecomers to the argument in 2008 noticed it because Obama was the second Democratic candidate to win a non-Southern Electoral College majority. Obama’s victory meant more because Clinton was a Southerner and was able to carry some states like Tennessee and Arkansas and Louisiana. Clinton didn’t need those states to get to 270 electoral votes but it did validate some who thought getting Southern voters was important. Obama did carry the three New South states – Florida, North Carolina and Virginia – and he even got more electoral votes from the South than Clinton did because he won big states. But he did it as a community organizer and an African-American coming from Chicago with an exotic background. A very non-Southern background.

The South is changing, and places like North Carolina and Virginia don’t fit the Whistling Past Dixie model the way they did 10 years ago, and that’s because of the infiltration of people who have moved there. The South is becoming more like the rest of the country. But as I say clearly in the book, one strategy is to wait 30 years until the differences between the regions don’t matter anymore. And if that’s your strategy, call me in 30 years. But if you want a majority now, and want to miss a generation or two of Republican rule, then you need to figure out how to do it without these voters and without these states. And Whistling Past Dixie was a path to do it.

Q. Political science isn’t a crystal ball. But considering the losses that Democrats took in 2010, and without knowing exactly which Republican candidate will be nominated, what will President Obama have to do to win reelection?

A: The one thing that Obama doesn’t have to do is improve his splits in any groups. The groups that he’s winning are growing and the groups that he’s losing are shrinking. The country is becoming less white, less married and more secular. All Obama needs is to get the same groups and the same shares, because their shares are getting larger. The only parts of the Democratic coalition that are shrinking are union families, basically, and some senior citizens, because of longevity as share of the electorate.

The reason for the defeats in 2010 has something to do with bad performance, and something to do with a rebuke of Obama, but it has a lot to do with the fact that the electorate in off-year elections is fundamentally different than it is in presidential election years. Younger and non-white and poorer people drop off in their turnout rates and older and whiter and more affluent voters turn out at higher rates.

Q. What are you working on now?

A: I’m working on a book on the history of the Republican Party between the end of the Reagan era in 1988 and the election of Obama in 2008. I was focusing on how the Republicans went from a party that won three presidential elections in a row – the only time that had happened in the past 60 years – to a party that just got destroyed in the 2008 elections, despite running against an African-American candidate with a funky name. In fact, as well as Obama did, the Democrats outperformed the Republicans in congressional races by an even wider margin, which shows that a lot of people voted for John McCain then voted for Democrats further down the ballot.

I’m writing the book in chronological order, and as I got into the Newt Gingrich era and the rise of the Congressional Republicans, I figured out I had the wrong focus. The Republicans have become a congressionalized party – and in particular a “House-ified” party. The GOP is a more House-tilted party than it has been in its history. The ratio of House seats to Senate seats for the Republicans is at an all-time high.

The Republicans made short term decisions that made sense and they were rewarded for them. Take racial gerrymandering. Creating majority/minority districts was a brilliant short-term strategy. Pack all the minorities into a few districts and we can win the rest of them. And there were a lot of Republicans and blacks elected to Congress in 1992 and 1994. But long term, it leads you to think that you don’t have to talk to the rest of the country. And the minorities that were six percent of the country when Eisenhower was elected in 1952 are now 26 percent of the electorate.

It has led to the decimation of the Republican Party – and especially on the presidential level. What does it say that four of the ten 2012 GOP candidates are or were House members? House members rarely get nominated for the presidency and even more rarely get elected. The last time it happened was James Garfield in 1880. So what it’s saying is that the Republicans are having a hard time generating saleable national figures from their governors and senators.

Choices by party elites and political leaders over the past two decades have reinforced that tilt toward the House – and increased the party’s self-marginalization until now it’s a conservative rump subset of the once proud and far-reaching national Republican Party.

Tags: Winter 2012