Travels and travails play a big part in award-winning UMBC historian Kate Brown’s highly-personal approach to investigating nuclear power and nationalism.

By David Glenn

A few years ago, historian Kate Brown spent several weeks in a tiny cottage in an obscure corner of Russia’s Ural Mountains. She was studying the history of Ozersk, a secret Soviet city built in the late 1940s to house the country’s first plutonium-processing plant.

Ozersk itself remains just as closed to outsiders in Vladimir Putin’s Russia as it was in Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union. So a cottage that Brown rented several miles outside the city’s gates turned out to be the closest she could get to the nuclear site.

“I would basically get up in the morning and chop the wood to take a shower,” says Brown, who is an associate professor of history at UMBC. “Carry the water in from the well. All of that stuff that you do in a village. And then I would wait for my cell phone to ring. My contact would say I have someone to meet with you – and then I would go and make my appointments.”

Brown met a number of elderly Ozersk residents who testified about the city’s early years, including a 1957 accident that released massive amounts of plutonium and led to the evacuation and destruction of more than 80 villages across the southern Urals. She also talked to younger activists who are struggling to force the Russian government to pay reparations for the slow-motion environmental devastation caused by plutonium production across the decades. Poking into the shadows of the Russian side of the Cold War decades, Brown still occasionally feared being detained or having her passport revoked.

Brown’s willingness to chop firewood or risk harassment to get closer to the history she writes is nothing new. In the late 1980s and early 1990s she traveled throughout the collapsing Soviet empire as she helped lead a glasnost-era student-exchange program. Today, at the age of 47, she commutes to UMBC by riding a bicycle across more than three miles of Washington traffic before getting on a train.

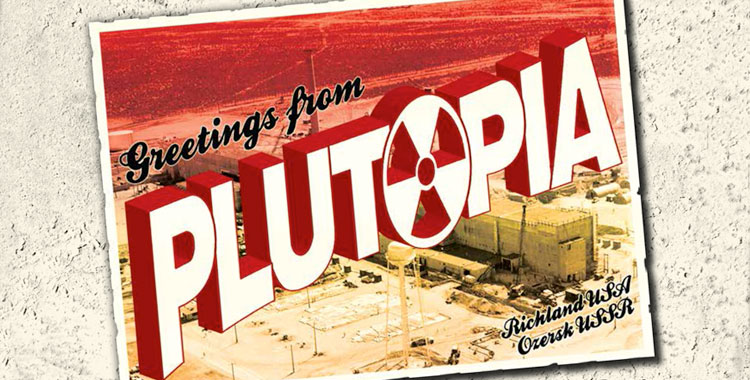

But colleagues and students observe that Brown’s physical intrepidness is matched (and even surpassed) by her willingness to take intellectual risks. For instance, her forthcoming book, Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (Oxford University Press) is a tale of two cities: Ozersk and Richland, a city in Washington state that abuts the first major U.S. plutonium facility at Hanford Nuclear Reservation.

Plutopia dives deep into the history of the military, medicine, labor, culture and the environment in both Cold War powers. Yet Brown makes few explicit comparisons or contrasts between these two cities themselves, structuring the book instead as a “tandem history” that allows the reader to use each city as a prism through which to view the other entity.

Brown also frequently inserts herself into the text, explaining how she cultivated relationships with certain informants or came to a dead end in certain archives. “Historians are reluctant to be a character in their own history,” she observes. “But the fact that we’re there affects what happens. I try to set it up in a way that I can tell a story that makes the exploration, the getting of the story, a part of the journey for the reader.”

Catherine Evtuhov, a professor of history at Georgetown University, is an admirer of how Brown marries an immediacy more often found in journalism (which is, after all, history’s first draft) to the rigor of the social sciences. “Kate does her work not in some kind of theoretical way,” Evtuhov argues, “but by going and spending a good deal of time in these places, getting people to discuss their histories. She brings some of the techniques of an investigative reporter.”

THREAT ASSESSMENTS

Brown became hooked on studying Russia during six months she spent living in Leningrad in 1987, when she was a senior at the University of Wisconsin.

“Strangers would come up to me on the street and say, ‘Go home and tell them that we just want peace, and that things just aren’t working,’” she recalls.

When the regime began to crumble a few years later, Brown was not surprised. The system she saw in 1987 already seemed like something dying. She recalls being horrified that the Reagan administration had built so many nuclear warheads to counter such a hollow threat.

After she completed her Russian major at Wisconsin, Brown took a job at a Middlebury College-based student exchange program. Among other responsibilities, Brown had to keep tabs on the safety of American students who had been placed in far-flung corners of the decaying empire, especially places that had featured in previous national rebellions against the Soviet state.

“I’d take trains to Ukraine or the Baltics,” she says. “And that’s when I noticed that the real force that was pulling the Soviet Union apart was nationalism. That took us by surprise. It seems stupid now, but the thought at the time was that nationality had been tucked away.”

Brown also argues that a new openness which made it no longer dangerous to publicly excavate and talk about past crimes – even those committed by the nation’s secret police – also helped destroy the Soviet Union. “People were digging up mass graves of people who had been killed by the NKVD,” she says. “Digging up buried stories at different sites; that really put the Soviet regime on the chopping block. They just couldn’t stand up to that. That was when I understood how much history matters.”

In 1992, Brown enrolled in the doctoral program in history at the University of Washington at Seattle, which houses one of the country’s most venerable centers for the study of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. She was ambitious, but retained diverse interests that included the study of anthropology, literature, and other fields, and freelance reporting for National Public Radio and other venues.

“I dragged it out as long as I could,” she recalls. “Any free summer or semester I could write a grant and go study Kazakh or Polish. It was just fabulous. I did a lot of traveling under the guise of language studies.”

Brown finished her program in 2000 and did a year of postdoctoral research at Harvard University before joining the faculty at UMBC in 2001. Her investigation into how ethnic Ukrainians, Poles, Jews, and Germans coexisted in the borderland region around Chernobyl – a region that was never consolidated into any particular nation-state before it was reconfigured by the Soviets and then invaded by the Nazis before being retaken once again by the Soviets – became the subject of her first book, A Biography of No Place: From Ethnic Borderland to Soviet Heartland, which was published by Harvard University Press in 2004.

As she does in her new book, Brown blended several different modes of historical writing (including personal narrative) in A Biography of No Place, which garnered multiple prizes (including the American Historical Association’s prestigious George Louis Beer Prize for modern European international history) and has proven influential among fellow historians.

Lynne Viola, a professor of history at the University of Toronto, had never heard of Brown before Harvard sent her the manuscript, requesting a blurb. “I was very irritated, because they hadn’t asked beforehand,” Viola says. “But I looked at the manuscript and got completely pulled in. By the time I finished, I had written to Harvard and asked how I could contact Kate Brown. Because I thought this was one of the most original things I’d ever read.”

PROBING THE PARALLELS

The research project that became Plutopia had an odd birth. Knowing of her interest in the Chernobyl region, several friends sent Brown links in 2004 to a website created by a Ukrainian who had traveled by motorcycle through villages that had been abandoned after the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Brown was intrigued by the website. Might those empty villages be an important time capsule? Would letters or other documents reveal whether the Soviet citizens of 1986 knew that their regime was on its last legs?

When Brown went to Ukraine to investigate, it soon became clear that the motorcyclist’s website was an elaborate hoax. But as she traveled around Chernobyl with a journalist friend who was writing about the fraud, Brown began to ponder a book on nuclear disasters.

“There was a period of time when nobody was interested in nuclear issues,” she says. “We were all exhausted with it, right? The Cold War was over. We didn’t have to think about this anymore. We had to think about it for so long in so many terrifying ways. I had definitely been in that frame of mind.”

The enduring – and, in many ways, still invisible – destruction surrounding Chernobyl changed Brown’s mind. She became fascinated by the story behind the Soviet plant at Ozersk, which was built in a muddy zone with few paved roads in 1947 as the Soviets scrambled to compete with the U.S. atomic weapons program.

The Ozersk plant suffered its own Chernobyl-sized calamity: the 1957 explosion that forced the evacuation of 87 villages in the southern Urals. But the shadowy site also offered the chance to relate the decades-long destruction of the environment as well, as the Ozersk plant sent irradiated water into rivers for many years.

As Brown pondered how to tell the tale of Ozersk and the Soviet nuclear industry, she also made a connection to the other side of the Cold War divide. While studying in Seattle in the 1990s, she had been gripped by news stories about the Clinton administration’s declassification of millions of documents that revealed the extent of environmental and public-health damage associated with plutonium production across eastern Washington.

“I thought about the Hanford site,” says Brown. And the similarities between two places so far apart and yet so parallel in design and in long-term environmental destruction became insistent to her.

“I thought, what people need to know about are these military sites that have been covered up for so long,” Brown says. “They’re so much more serious in terms of environmental catastrophe than this one-off event at Chernobyl.”

COVERT CONVERSATIONS

So Brown set off on what became a six-year project, supported in part by a Guggenheim fellowship and a grant from the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research. (Brown also had support for the book from the Kennan Institute, and received a collaborative grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.) She pored over Cold War documents at the U.S. Department of Energy and the regional Communist Party headquarters in Chelyabinsk, but also spent many months in close proximity to both sites.

In the Urals, elderly Ozersk residents shared a mixture of baroque horror stories – thousands of young workers retiring because of radiation poisoning – mixed with intense nostalgia. Though it didn’t appear on any maps, Ozersk was known as the nicest place to live in the southern Urals. Soviet authorities provided the city with parks, schools, medical care, and consumer goods that were far above the nation’s usual level. After the terrors of Stalin and World War II, Brezhnev-era Ozersk seemed like paradise.

Brown also canvassed eastern Washington state to find proud veterans of the Hanford plants and “downwinder” activists who believe plutonium contamination has caused many cancers and birth defects.

As was the case with Ozersk, Brown discovered that Richland’s proximity to the Hanford facility made it a seeming oasis of prosperity amid rural poverty. The corporate contractors who built and operated the Hanford site – Du Pont in the early years, and later General Electric – self-consciously created a “classless” model community where both nuclear engineers and blue-collar factory workers could live in single-family homes and enjoy consumer abundance.

Both the U.S. and Soviet governments used that abundance to help elite scientists reconcile themselves to lives in remote provinces. But Brown also points out that both Richland and Ozersk were anything but classless: In different ways, both plutonium complexes consigned their lowest-level workers to hardscrabble lives on the periphery.

Economic concerns were matched by both governments’ concerns about security. As the two cities evolved across the 1950s, their creators were intensely aware of each other – and even in a sort of dialogue across borders. Brown says that the questions each side asked were fundamental: “What are they doing over there? How can we do it better over here? What do we need to do to prevent them from getting our secrets or attacking us? So they’re very much in conversation with one another, but the conversation is sometimes covert.”

Brown worked hard to keep Plutopia as clear as possible, even though the book moves across national borders and contains material about a vast array of topics.

“I don’t intend to compare the cities,” Brown continues. “What I want to do is place them alongside one another, and to show how sometimes enemies that are intensely opposed to one another start to look like one another because of the force of that focus.”

LOCATING HISTORY

Getting physically close to the locales about which she writes is key to Brown’s method as a historian. Focusing on a place, she believes, allows historians to combine political, social, and scientific history in powerful ways.

“You can do all of that when you start from a place,” she says. “By circumscribing the territory you’re looking at, you can transcend these boundaries that we’ve created in these subfields of history.”

Brown pushes her students at UMBC, especially those in the master’s degree program, to pursue similarly placebased projects. To immerse them in that method, this year she is leading one class in a review of the archives of the Neighborhood Design Center, a Baltimore-based organization of activist urban planners and architects.

“Dr. Brown is incredibly supportive, but she will not hold your hand,” says Rhiannon Dowling Fredericks ’09, M.A., history, who is now in the doctoral program at the University of California at Berkeley. “She wanted us to have projects that were reasonably finished before she would review them with us. But once we got to that stage, she would have amazing suggestions about how we could expand our projects and move forward.

In moving her own work forward, Brown is now assembling a collection of historical essays tentatively titled Being There. “I hope to use this as a call to arms for doing place-based history,” she says.

She also hopes to persuade younger historians to become more comfortable with occasionally using the first person, so that they can be more candid with readers about their own biases and about the twists and turns that their research has taken.

“These stories don’t just come out of nowhere,” argues Brown. “And we’re not a god-eye looking from above. We’re on the ground. We, too, are in play.”

In the meantime, Brown is preparing for the publication of Plutopia this spring.

“What Kate has done has not been easy,” says Lynne Viola, of Toronto. “A Biography of No Place really inspired many people, and I expect that the new one will too. I think it will have a very large impact on younger scholars.”

For her part, Brown is grateful that she took that trip to Leningrad in 1987. The region has been a consuming obsession for her for the last quarter century. “It has been a wild ride,” she says, “watching this country blow itself up, put itself back together again, feud over the component parts—and now Putin is consolidating power in a way that sure feels like the Soviet Union wedded to the czarist empire. It’s been just fascinating.”

* * * *

One of the strengths of Kate Brown’s Plutopia is its sense of finding history in geography – as she does in describing a visit to Hanford in the book’s second chapter:

Gerber showed me with a sweep of her arm the site of the former Hanford Camp, set up in 1943 to house workers building the plutonium plant. I nodded unthinkingly and then looked again. She was pointing at emptiness: a flat plane, laser-graded, a few trees weakly prodding the sky. Staring, I began to make out the faint outline of streets converging at right angles. Western ghost towns usually have a few walls standing, foundations that outline a saloon or bank. This site had been expunged almost fully, although in its day the camp had been a city of 60,000 people, and for a few months had the state’s fifth largest population. Dining halls, barracks, stores, barber shops, theaters, taverns, a roller rink, dance pavilion, swimming pool, bowling alley, bank, hospital, and the state’s busiest bus depot and post office had all once stood on this site. It had been a vast camp that never slept, with round the clock shifts, or rather a place that always slept, as graveyard workers sank their blinds and hoped for quiet amidst the constant rumble of machinery. Hanford Camp went up in a few months in 1943 and disappeared in a few months in 1945. This teeming city stood all of twenty-three months, and a half-century later had vaporized back to desert.

From Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (Oxford University Press)

Tags: Winter 2013