We’ve all had these moments.

Moments of wondering aloud. Moments of principled argument over sandwiches in The Commons. Moments of listening and believing as someone’s personal truth unfolds before you. Moments of examining our ideals and acting upon them.

Humanity strives for truth, but it’s not such an easy thing to achieve. Barriers can keep us from it. (Sometimes we are our own worst barriers, in fact.) But we persist in breaking through, in not shying away. And we nurture each other as we figure things out.

In his State of the University address this fall, UMBC President Freeman Hrabowski noted, “We are a community that believes in the importance of having respect for each other and seeking the truth. Nothing we do at UMBC is more important than the search for truth, and our role in teaching students how to think critically.”

You can’t have truth without light. This is a community where that light burns brightly.

These are but a few of our community’s ways of approaching tough questions. These are our

MOMENTS OF TRUTH.

Moment #1: Questioning Everything — Math + Philosophy = Doubt

Moment #2: Committing to Print — Beyond Black & White

Moment #3: Examining Our Biases — Seeking Honesty in Collections

Moment #4: Seeking the Truth — Science and Faith

Moment #5: Creating Safe Spaces — Seen and Believed

Moments #6-11: Walking the Talk — Words Become Actions

Moment #12: Listening to Our Instincts — The Computer is (Not) Always Right

Moment #13: All Voices Welcome — Conversations We Avoid Over Thanksgiving Dinner

Moment #14: Being Ourselves, for Ourselves and Strangers — Our (Secret) Truths

Moment #1.

Questioning Everything

MATH + PHILOSOPHY = DOUBT

For those who think college is just about sitting in a lecture hall, listening to a professor profess, absorbing what they hear, and leaving with a brain full of absolutes, we humbly turn your attention to the far corner of the room.

As a mathematician, professor, and novelist Manil Suri wants his students to question everything they hear; as a philosopher, instructor Jim Thomas desires the same. So, when they talk with their classes about representations of truth in their fields — proofs, axioms, facts, and the like — they sometimes bend it a bit just for the sake of argument.

Suri likes to start his 301 class with a proof that seems right…until it suddenly doesn’t. The students realize they’re trying earnestly to prove that any whole number, like 1, 2, 3, etc., equals any other possible whole number.

“And I say, ‘Do you know what this is saying? Do you think there might be something wrong with it?’ And so then they scramble to try and find what could be wrong,” he says.

Thomas approaches his intro students in similar fashion, telling them a series of truths about himself when he first meets them, then building into statements that could or could not be believable, and then laying it on a bit thicker. He’ll say he’s in his 70s, for instance (which he most certainly is not), but with a truly double take-inducing deadpan.

It’s all part of how they teach their students to think deeply about two subjects known for building off of deceptively simple ideas. One plus one equals two, but it can take hundreds of pages to prove that equation. Philosophy hopes to create a truthful description of the world, but anyone studying it long enough eventually realizes how naive the pursuit is, Thomas says: there’s so much standing in the way of answers.

“I say, ‘Of course, it’s a word. I wrote it on the board, so that’s a word.’

And so now they’re thinking, ‘Why am I trusting this?’”

— Jim Thomas, philosophy instructor

The best way of moving forward is to doubt everything, the two agree, discussing it upon meeting for the first time.

“Any kind of proposition that’s given to you, the only way you can actually get to a proof — even when it’s true — is to try and think how it might be false and to hurl all these possibilities at it, and try to see if there’s a chink somewhere that things don’t work out,” says Suri. “And that’s a super-concentrated version of the same kind of skepticism we increasingly need in day-to-day life.”

And so Thomas’s way of purposely misspelling words on the whiteboard to see if anyone calls him out on it isn’t just some kooky professor trick, but a way of kickstarting that doubt in his students.

“I say, ‘Of course, it’s a word. I wrote it on the board, so that’s a word.’ And so now they’re thinking, ‘Why am I trusting this?’” says Thomas. “I want them to doubt whether or not they know the truth, and I want them to doubt it so they understand that the truth is something that is worth the trouble.”

— Jenny O’Grady

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

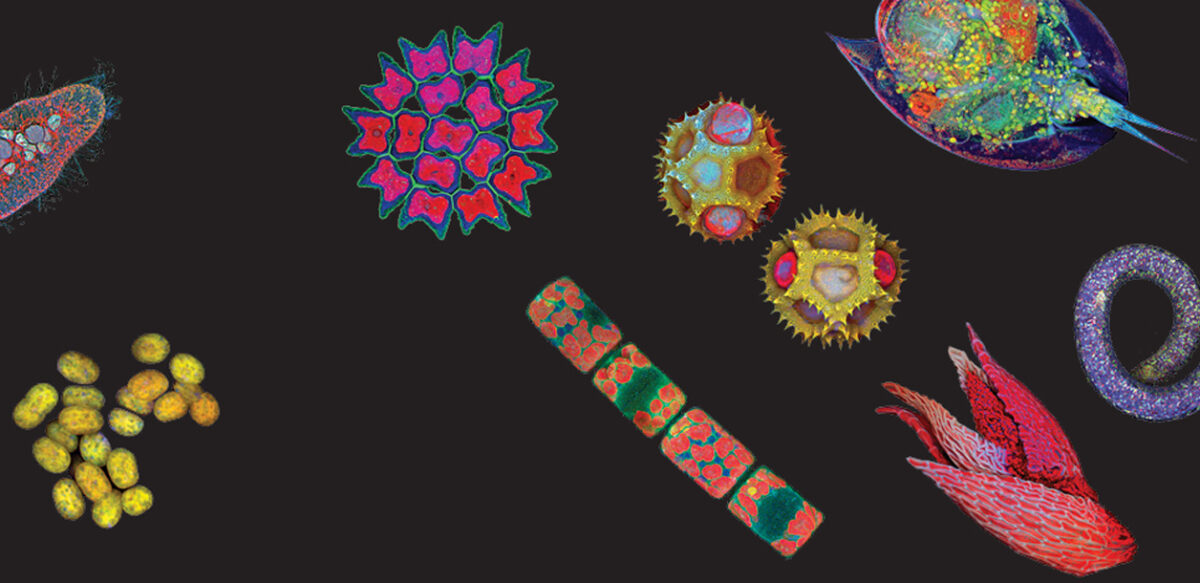

Moment #2.

Committing to Print

BEYOND BLACK & WHITE

The Retriever, UMBC’s student newspaper since 1966, has always had something to say. Above the fold, the very first paper of this fall semester declared its intentions in bold inch-high type:

We Commit.

To Truth. To Community. To You.

“We decided we needed to make a statement and re-commit to what we stand for as an organization,” said current editor-in-chief Julia Arbutus ’20, a double major in English and financial economics.

People noticed. And as the semester has progressed, with all of the twists and turns of news on campus, the student reporters have stretched themselves to learn and grow — a process repeated many times over since the paper first published in its original form as UMBC News in September 1966.

Joseph Howley ’06, ancient studies, served as a reporter and editor during a period of time that included upsets in fraternity leadership, a murder case involving a former student, and the beginnings of the war in Iraq. During that time, he and his staff strove to create a publication that helped students understand what was going on in the world around them, he said.

“An independent student press may be the only organization on campus equipped and motivated to challenge those institutions and make sure that students know what they need to about how they are or are not looking out for them,” said Howley, now an associate professor of classics at Columbia University.

“I hoped for this type of impact, but I didn’t know how

widespread it would be.” — Julia Arbutus ’20

Former news editor Tyler Lewis ’18, political science, learned skills during his years at The Retriever that are serving him now as an intern on Capitol Hill.

“Working as a student journalist provided the perfect opportunity to sit down with important members of the community,” he said. “The more I networked, the more scoops I received, and consequently I was able to better fulfill my goal of writing meaningful stories that mattered to my audience.”

As a scholar and a budding journalist, Arbutus takes the job of telling the truth very seriously. When that first issue hit the stands, she got an immediate rush of support from students, as well as alums of the paper, she said.

“I hoped for this type of impact, but I didn’t know how widespread it would be,” she said. “[This is] a movement to channel our journalism into more student-focused stories and to find a more active place within the student body on campus. We really want students to be proud of and engage with their community newspaper.”

— Jenny O’Grady

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

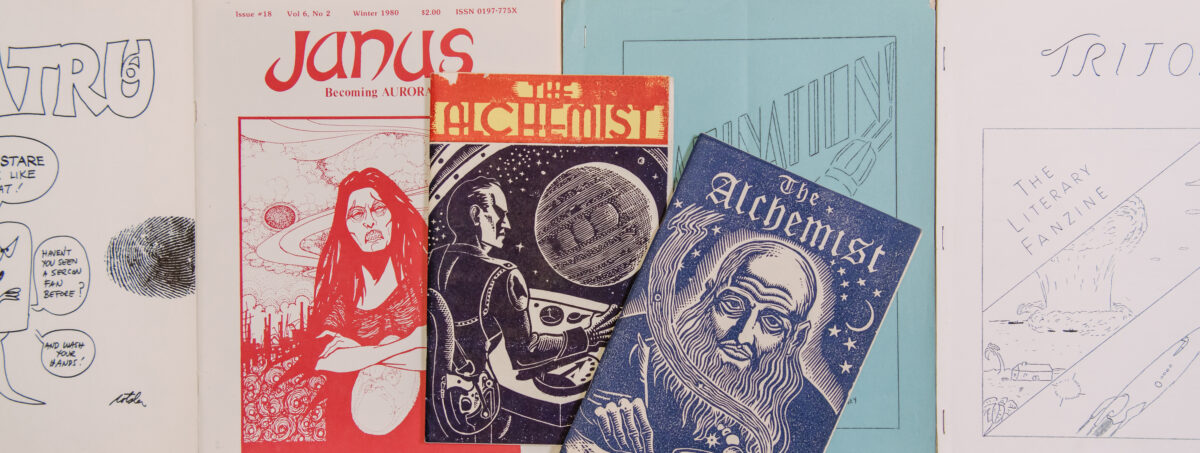

Moment #3.

Examining Our Biases

SEEKING HONESTY IN COLLECTIONS

The tagline for the television show The X-Files proclaimed that “the truth is out there.” Once a week, true-believer Fox Mulder and sceptic Dana Scully probed the possibility of hidden realms of the paranormal and conspiratorial lurking beneath the surface of American society. Faced with current cultural debates, the tagline seems less a tongue-in-cheek credo than a desperate plea to restore a once verifiable truth that is now elusive; the truth is out there, somewhere, surely, but where? While it is easier than ever to access information, it seems harder to decipher the significant fact from the extraneous detail.

“We must also interrogate how these objects came together in a collection

in the first place, since what is excluded can tell us just as

much as what is included.” — Beth Saunders

I come from the world of museums, where provenance is a major key to unlocking information about an object. Knowing where something came from and who else may have viewed, valued, or owned it tells us a great deal about objects, but also about history. I would argue that we could all benefit from thinking more about the provenance of the information we encounter. Museum and library collections make it possible to trace information to its origin by providing access to primary sources. Evaluating subsequent interpretations against the original text illuminates the biases that each researcher necessarily brings to the material. However, we must also interrogate how these objects came together in a collection in the first place, since what is excluded can tell us just as much as what is included. The truth is indeed out there, if you are willing to look for it.

— Beth Saunders, curator and head of Special Collections and Gallery

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

Moment #4.

Seeking the Truth

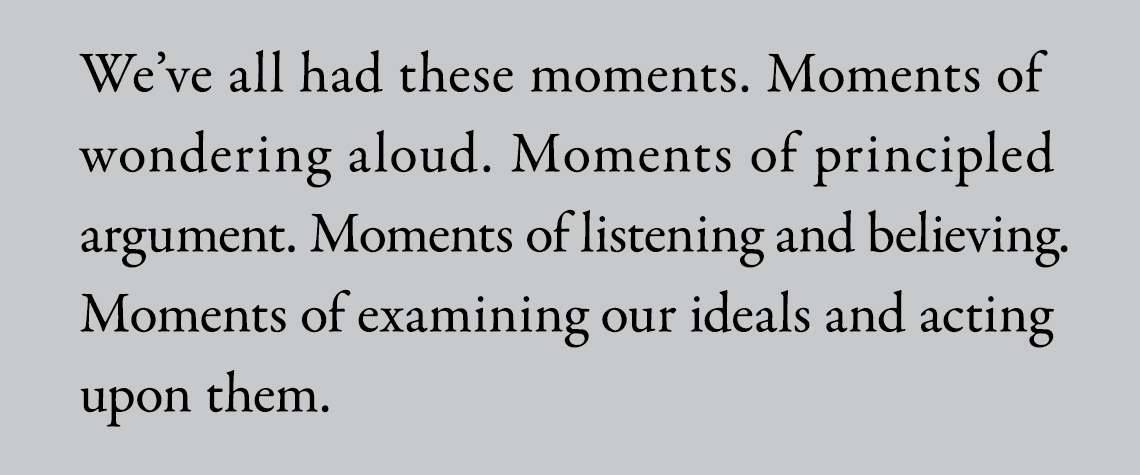

SCIENCE AND FAITH

“Science is a systematic process that seeks to understand the inner workings of the universe, our world, and ourselves,” says Bill LaCourse, dean of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences at UMBC. In other words, it is a process that seeks the truth — not a static body of facts. Scientists rely on observations and experiments to reveal and then repeatedly confirm truths about the world, but no conclusions they draw are ever guaranteed to be the last word.

It’s that uncertainty, the apparent fleeting nature of what is true, that may lead some people to toss science aside as unreliable or even misleading. That’s why it’s so important that the practice of science be communicated in a way that helps people understand its strengths alongside its limitations.

One of those limitations is that science is a human endeavor. As such, it is not as pure or objective as we might like to believe. “Science is a search for truth that relies on observations by humans and all their inherent qualities, whether righteous or flawed,” says LaCourse. Steve Freeland, an astrobiologist and director of the Individualized Study Program (formerly known as Interdisciplinary Studies) at UMBC, adds, “Scientists are partly responsible for creating what they observe in ways we still do not fully understand.” In other words, who does the science, despite their best intentions to be objective, influences what truths are discovered.

But the scientific method is not the only way to seek the truth. “Twentiethcentury scholarship, from within and beyond science, has led us to a current understanding that no one approach to finding truth is superior or sufficient,” says Freeland, who is also a committed Christian. “Logical systems must always be incomplete in terms of what they describe,” he adds. “This gives each of us reasons for humility as we seek truth in our different ways.” The scientific method, religious traditions, spiritual practices, and Indigenous traditional knowledge are all valid ways of seeking truth.

However, it is easy to distrust knowledge gained by means one does not understand. In particular, the uncertainties and impurities inherent to the scientific enterprise can influence how it is perceived by people more familiar with other truth-seeking methods, especially if they are more absolute in their profession of what the truth is. And yet, it is critical that scientists and people of faith communicate across their differences if we are to build a just, safe, and healthy world for all.

“In the end, the search for truth will be a collective journey of many by many roads,

humbled by our own ignorance and glorified by a common goal.”

— CNMS Dean Bill LaCourse

In March, UMBC will offer our community the chance to explore the tricky terrain that is communication among science and faith communities. UMBC is one of six universities nationwide selected by the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Dialog on Science, Ethics, and Religion to organize two days of events around this topic. LaCourse, Freeland, and STEM communications manager Sarah Hansen lead the UMBC team organizing the workshop.

Researchers will receive training on how to communicate with people of faith in ways that constructively engage them while also respecting their identities and worldviews. That includes finding ways to show people of all backgrounds how recognizing the value of science — but not necessarily its primacy — aligns with their values, such as being stewards of the Earth or protecting the vulnerable. The event will also allow scientists an opportunity to familiarize themselves with other means of truth-seeking, and learn how to avoid alienating people by invalidating those methods in conversation.

“In the end, the search for truth will be a collective journey of many by many roads, humbled by our own ignorance and glorified by a common goal,” says LaCourse. As Karl Popper, renowned secular philosopher, put it, “Our attempts to see and to find the truth are not final, but open to improvement… criticism and discussion are our only means of getting nearer to the truth.”

— Sarah Hansen M.S. ’15

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

Moment #5.

Creating Safe Spaces

SEEN AND BELIEVED

“Is it my fault?”

“What just happened?”

“Is it rape?”

“Am I just making a big deal out of this?”

These are the questions we hear on a daily basis in the Women’s Center. UMBC community members — whether current students, alumni, faculty, or staff — tell us their truths, despite their own misgivings about the efficacy of that truth.

This self-doubt is common among survivors of sexual violence. And, so we tell them: We believe you. We see you. You matter.

In the wake of trauma and abuses of power, many question the veracity of their experiences and the impact that it has had on them. Whether a person has faced emotional, physical, psychological, social, or economic abuse, we see the impact clearly in the fear and misplaced self-doubt that surround them like dark clouds. Sometimes, coming to the Women’s Center is the first time a student feels believed or validated. Even as we work through resources meant to help and guide people towards healing, these misgivings continue interrupting every aspect of recovery.

And this work is complex.

Our community is not just made up of survivors puzzling through their experiences for the first time. Healing is not, as much as we may want it to be, linear. And, so we also support survivors as they face instances of re-traumatization, as they navigate the frustrating and often disappointing process of seeking justice, and as they practice coping skills in a culture that often does not lend itself to healing.

“There is power in naming our experiences and truths as a shared collective and

this is what we have been called to do in this moment on our campus.”

— Jess Myers and Amelia Meman ’15

Our job in the Women’s Center is to create space for truth-telling. This has been our role since our founding in 1991 as a small, volunteer-led operation. We were born in the wake of Anita Hill’s testimony where she spoke her truth about sexual harassment, and which then allowed so many other women to come forward with their own experiences.

There is power in naming our experiences and truths as a shared collective and this is what we have been called to do in this moment on our campus. As UMBC wrestles with the reality of a civil lawsuit that has forced us to examine the ways we listen to and support survivors of sexual violence, we are given a renewed opportunity to bring a light to truth and help foster a campus that is survivor-centered.

For the last 27 years, our job in the Women’s Center has been to create space for truth-telling by supporting survivors of all genders through individualized support, events like Take Back the Night, educational workshops, and advising the We Believe You student organization, but our real goal is ultimately to work ourselves out of the job. What would it look like if our campus community was so dedicated to sexual violence prevention work that the Women’s Center no longer needed to operate? What are the doubts and truths within ourselves that we need to explore to get there as a campus community? These are the questions we ask ourselves every day and we hope that in this chaotic time, more of us will have the courage to join us in this culture changing work.

— Jess Myers, director, and Amelia Meman ’15, program coordinator, UMBC Women’s Center For more information about the Women’s Center and its services for the many UMBC communities it supports, visit womenscenter.umbc.edu.

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

Moments #6-11.

Walking the Talk

WORDS BECOME ACTIONS

“It’s much easier to help others when you yourself are okay with asking for help. My hope is that by empowering others to ask for help, they will be more willing to give help in the future. Students seem to be very responsive to this. I’ve developed a relationship with many of my residents because I helped them out of a tight spot just once. Later on, they’ve helped me carry stuff up to my room, cleaned up after a program, and other small acts that really mean a lot to me. By cultivating a culture of high support, we can empower others to ask for help and give help. I’ve found that this principle is much less about knowing exactly what to do in every situation, and more about being willing to participate in the community of support.”

Lauren Whittaker is lead resident assistant in Erickson Hall, responsible for 50 students and 11 other R.A.s in the building. As a junior on the pre-physician’s assistant track, she is studying biological sciences with a psychology minor.

“I myself am a survivor of sexual assault and I know how traumatizing that can be to experience, and that really motivates me to make sure the school is doing everything it can to support survivors as well as enacting preventative measures. It is important to feel empowered because literally everything is malleable, even the things they say are not changeable are changeable with enough drive and support. Without people advocating during every step of the process, change ceases to happen.”

John Platter is a junior studying psychology, and a member of the LGBTQ Student Union, as well as various campus groups such as STOPP and UMBC Progressives.

“I have been working with people who have experienced assault since 2002 and have heard many stories. I have learned that there is no ‘right’ way to respond to an assault. People’s responses to an assault, and what they need to feel supported following assault, vary hugely. Some want to talk about the assault to whomever will listen. Some never tell anyone. Some seem relatively unaffected, whereas others seem shattered. And these responses often change over time. People may seem fine right after a traumatic event and then become more distressed months or years later. It’s often not possible to predict what someone who has been assaulted will need, and usually what we see as observers is just a piece of what’s happening inside someone after an assault. I have learned that the only way to know how to support survivors is to listen to them, and listen closely. Sometimes this means putting aside my anger when I hear about injustice and harm that someone has suffered so that I can stay focused on providing the support that they’re asking for — in short, allowing survivors to define their experience for themselves and ask for what they want.”

Rebecca Schacht is a clinical psychologist who serves as director of the UMBC Psychology Training Clinic. She is also an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology.

“In an environment where student-athletes are expected to be physically and mentally strong, it can be hard for them to ask for help. I feel honored when they seek me out for assistance. They trust me to help guide them through a challenging situation and I do my best to help them navigate the environment. It is important for community members who work closely with students to feel comfortable being an advocate. Even if you don’t know the right answer, you probably know someone who does. And to that student, the first phone call makes all the difference.”

Jessica Hammond-Graf advises student-athletes in her role as senior associate athletic director at UMBC.

“One of my favorite opportunities to connect with students is through Green Dot, which teaches community members that as bystanders we have a responsibility to keep each other safe. Community members learn how to identify behaviors related to stalking, partner violence, and sexual assault and then act by being direct, distracting, or delegating to someone more equipped to help. Nobody has to do everything, but everyone has to do something! I think people get overwhelmed by the idea of intervening as if it has to be a superhero gesture — where you put on a cape and take down the ‘bad guys.’ Intervening can be a simple moment in time where you ask someone if they’d like to talk or share some behavior that you have observed. Most of us can think about a moment, big or small, where we could have really benefited from someone stepping in to help us. How great it would feel to have confidence that the people around you, both friends and strangers, have an interest in keeping everyone safe. I believe that when thoughtful citizens learn the skills to do this, we can change UMBC and the world.”

Jacki Stone runs UMBC’s Green Dot training program, and serves as a community health and safety specialist in UMBC’s Division of Student Affairs.

“My work often involves feelings of excitement, frustration, sadness, hurt, joy, and fulfillment. These feelings at times can happen at once in the one hour I’m sitting with the student trying to navigate the process of understanding their needs, finding the resources, calling, advocating and connecting them to the resources. Some days the process is easy and straightforward and I have answers right away. Other times it feels like I am jumping hoops and moving mountains. We are in the business of higher education, meaning we are in the role of getting these individuals educated, with degrees to be productive members of society. They can’t get to the finish line if we don’t help them with the many hurdles along the way….and model behaviors that show empowerment and value social justice.”

Doha Chibani is a clinical social worker in UMBC’s Counseling Center and a 2008 alumna of UMBC’s psychology program.

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

Moment #12.

Listening to Our Instincts

THE COMPUTER IS (NOT) ALWAYS RIGHT

Each day, we interact with content in a range of forms, and rely on technology for everything from communicating and navigating our travels, to staying updated on the news and paying bills. Richard Forno, assistant director of UMBC’s Center for Cybersecurity and senior lecturer of computer science and electrical engineering, says people should take any information they find online with a grain of salt until they can verify it. Just because something is on the internet, Forno explains, does not mean that it is true or accurate.

Technology, however, is not solely to blame. “It’s a function, I think, of education and society teaching people to put faith in technology before their own selves,” he says.

Forno recommends that people do their own fact checking and listen to their instincts. “A good rule of thumb is if you hear something or receive something online, that before you get your emotions all tied up in knots, is anybody else reporting on this?”

As an educator, Forno feels it is his responsibility to educate UMBC students on how to think critically. “This all ties back to the idea of thinking critically and thinking for yourself, and not just blindly relying on what you’re presented with as information,” Forno explains. It’s also important that people who post to social media accounts be aware of the content they are sharing with their followers.

“This all ties back to the idea of thinking critically and thinking for yourself,

and not just blindly relying on what you’re presented with as

information.” — Richard Forno

“Recognizing that by just blindly passing something along on Twitter, you’re contributing to the noise machine, and you’re making the problem worse,” he says. “I know in my case, there were times where I’ve seen stuff on Twitter that I’ve been caught in a moment of weakness, and went ‘Oh, retweet. Stop.’ Then look through it, and say ‘No, I’m not going to play this.’”

The notion that the “computer is always right” can be challenging for consumers of media and information to work against because some images and videos circulating online can be very convincing. That’s why taking courses in a wide range of disciplines is so helpful for students shaping their perspectives, Forno says. “Things like civics and media literacy, digital cybersecurity — there’s a need for that so that you become a well-rounded and competent citizen.”

— Megan Hanks

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

Moment #13.

All Voices Welcome

CONVERSATIONS WE AVOID OVER THANKSGIVING DINNER

The old adage says there are three things one should never talk about: religion, money, and politics. However, avoiding certain topics instead of facing them head on can lead to divisiveness, and a lack of forward momentum.

As Romy Hübler, assistant director of the Center for Democracy and Civic Life, explains, “That goes against the idea of coming together and thinking about our own experiences and acknowledging the issues we’re all facing in order to truly address them.”

As a campus, the way to ensure that each community member’s truth is heard and respected is by placing the emphasis on collaboration and conversation, not individualization. Vrinda Deshpande ’20, executive vice president of the Student Government Association, recently worked with peers and several campus constituents to organize a “Dinner with Friends,” where guests talked about Maryland state and local politics at 10 simultaneous dinners, drawing conversation from their personal experiences.

While the student voice is important, students may not necessarily recognize that. “The biggest thing I hear from my fellow students is that as an undergraduate student, I’m not qualified to be part of certain conversations,” says Deshpande. “But undergraduate students make up the majority of the campus so a lot of the policy and decisions affect us directly.”

Similarly, in 2016 UMBC’s chapters of College Democrats and College Republicans began hosting “Coffee and Conversation” events — forums intended to appeal to all students, not just those who previously engaged in civil discourse, the organizers say.

“We want to help mend the social fabric and move away from the

divisive rhetoric that we see in our society today.” — Scott Buchan ’20

This year’s topic was healthcare, chosen because “we found the issue to be extremely relevant to the current election cycle and a contentious topic of the same nature as past topics (e.g., immigration, gun control),” explained College Democrats president, Luis Zuluaga-Orozco ’18, political science and media and communication studies.

Representatives from the Maryland Citizens’ Health Initiative and the Heartland Institute opened the event with remarks and then allowed the audience to steer the conversation, with lots of interaction in small groups. “We hope that the people coming out walk away with a better understanding of their peers and those who think differently than them and that they find that they can get along,” says Scott Buchan ’20, political science, College Republicans president. “So much emphasis is put on political beliefs that people are cutting off their friends who think differently. We want to help mend the social fabric and move away from the divisive rhetoric that we see in our society today.”

— Kait McCaffrey

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

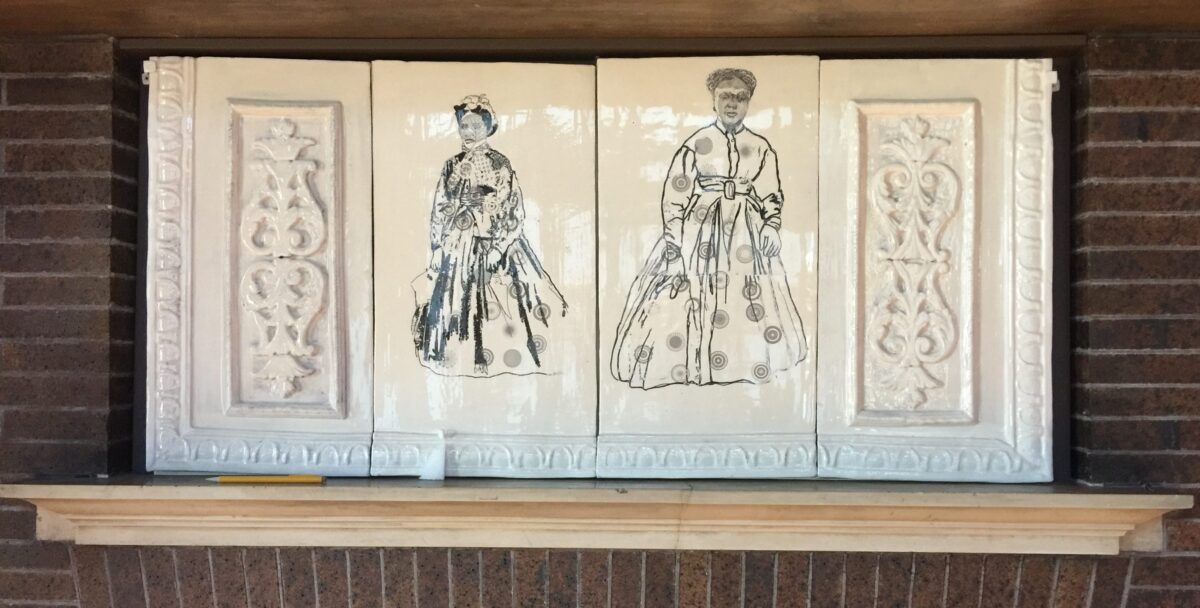

Moment #14.

Being Ourselves, for Ourselves and Strangers

OUR (SECRET) TRUTHS

Tucked away in a thicket of trees at the edge of campus, a seemingly ordinary notebook holds hundreds of tales of heartbreak, euphoria, angst, and love. The journal is housed beneath a bench in the Joseph Beuys Sculpture Park and serves as a blank slate for any passerby who has a story to tell.

In a world that lives almost entirely online through platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and Tumblr, the idea of taking pen to paper seems almost archaic. However, members of the UMBC community have shared their most private, oftentimes anonymous, truths in this highly public forum for nearly two decades now.

“If everybody keeps it secret, those who really need it may never find it.”

— Sandra Abbott, Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture

Once each journal is filled, it is collected and added to the tome that’s been steadily growing since the early 2000s, each serving as its own sort of time capsule. Brandee Blumenthal ’20, economics, is spending her semester working in the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture (CADVC) to scan and archive the collection of journals. She reflects on how this project manages to thrive in a digital world explaining, “The notion of journaling is something we all still grew up with. There’s something about writing on paper that feels different than typing it. You’re actually creating the words. For some people, it’s nostalgic and provides an element of comfort and familiarity.”

Sandra Abbott, curator of collections and outreach for the CADVC, cites the physical location as a reason for inspiration.

“You’re in a place that’s lush and green and cut off from the hustle and bustle of campus. It forces you to slow down. Handwriting takes longer, but that’s because you have to choose your words carefully and critically since you can’t go back and edit. It gives more weight to your words because you’re being intentional.”

While individuals may put their thoughts to paper and be done with them, that doesn’t mean their story is over. Many entries have annotated words of support or congratulations or commiseration from strangers flipping through the pages. Using the journals as inspiration, Linehan music composition majors performed “Creative Acts,” a site-specific music and dance production. A few students have even used the journal to take a major next step in their lives.

Nate Dissmeyer ’07, information systems management, had his unofficial first date with his wife in the Joseph Beuys Sculpture Park. When the time came to propose to his wife, he “grabbed the journal and suggested she leave an entry about us. While she was writing, I was able to pull out the ring from my pocket and get down on my knee and add that she should include this moment in the journal.”

With more attention being paid to the Joseph Beuys Sculpture Park’s treasures, is there a concern that this hidden gem will lose its luster? “I’ve always been divided because it’s a place that people discover on their own and it’s so special,” said Abbott. “But if everybody keeps it secret, those who really need it may never find it. We want the campus to take advantage of this space. It’s theirs.”

— Kait McCaffrey

Jump to Moment #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6-11 #12 #13 #14 Back to Top

Tags: Fall 2018