Michelle Scott reminisces about her grandmother’s tradition to call her grandchildren when they turned 18. “She’d call, wish us a happy birthday, and then ask if we had registered to vote.” If they hadn’t, they were asked to call back after registering.

“My grandmother knew the power of the vote,” remembers Scott, associate professor of history, and affiliate in the departments of Africana Studies and Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies. “She understood voting was not just about having the privilege to vote for the president but also about voting on local issues.”

“Not the beginning or the end”

The year 2020 marks the centennial of the 19th Amendment which enfranchised women. “It’s important to remember that suffrage was a push for that more perfect equality for women; it wasn’t the beginning or the end,” explains Amy Froide, professor and chair of UMBC’s history department.

Voting was almost not included in the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, the nation’s first women’s rights conference, explains Froide. Most salient to women were the right to access higher education, hold property, manage their own wages, and be able to get a divorce, and retain custody of their children. “It wasn’t until the late 1800s that women realized the vote would help them attain these rights,” says Froide.

Another thing not included at the convention were the voices of Black women. With the exception of Frederick Douglass, only white people were invited. Scott, an expert in Black women’s history; Froide, an expert in British history and European women’s history; and Susan Sterett, professor of public policy, acknowledge how systemic racism plagued the women’s rights movement from its inauguration.

Sharing lived experiences

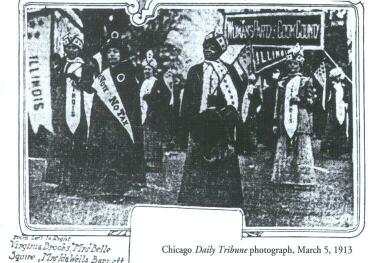

“Even today, celebrations about the 19th Amendment disregard the Black women who contributed to enfranchisement,” explains Scott. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett,” says Scott, who researches her anti-lynching work, “founded the Alpha Suffrage Club for African-American women in 1913.” Some of the other Black women are Frances Ellen Watkins Harper whose speech “We Are All Bound Up Together” was delivered at the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention of 1866. And Mary Church Terrell delivered her address “The Progress of Colored Women” at the 1898 National American Woman Suffrage Association.

To help students gain a greater perspective of what these women were up against Scott uses storytelling as a strategy. “My grandmother was an excellent storyteller,” shares Scott. “I learned a lot about her life through her stories.” Her grandmother, Marion Vincent, was born in Baton Rouge in 1919. When she was of legal age to vote Vincent was prevented from voting due to voter suppression tactics. She moved to California where she was eventually able to vote, almost 70 years after the 19th amendment was ratified.

“There was massive disenfranchisement of African Americans before the 1965 Voting Rights Act,” explains Sterett. Sharing lived experiences like Scott’s grandmother’s helps students understand the complexity of implementing constitutional law.

All three see a great need for scholarship on the contributions of Black, brown, and indigenous women leaders in the suffrage movement. The centennial can be an opportunity for this work.

Shaping the future

Maureen Evans Arthurs ’13, gender and women’s studies, agrees. Recounting her matriarchal lineage, Evans Arthurs names her family members that laid the foundation for her unique position today. Her great-grandmother, Pearl Johnson, was born to sharecroppers in 1887. Her grandmother, Irene Shepard, was born in 1918. Evans Arthurs’ mom, Renee Smith Guelce, was born in 1956. “I was born in 1986. My sister was born in 1982. We are the first people in my family to grow up with the birth right to vote.”

Evans Arthurs voted for the first time in 2004, 84 years after the 19th Amendment was ratified. Today, she is the director of government affairs for Howard County Government, helping shape the future for the next generation.

*****

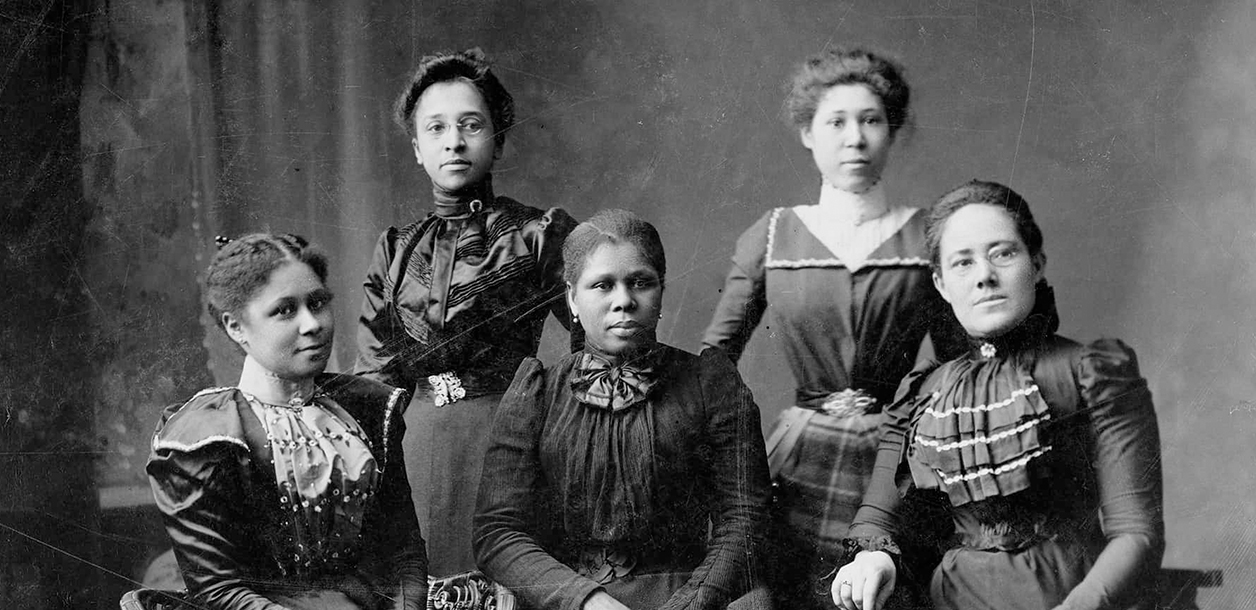

Header image: Five women officers of the Women’s League in Newport, Rhode Island, c. 1899. Source: National Women’s History Museum.

Tags: CAHSS, Fall 2020, professorsnottomiss