THE BODY ELECTRIC

Monitoring significant developments in a patient’s health outside a hospital can be challenging, but two UMBC researchers – Tinoosh Mohsenin and Gymama Slaughter – have won separate grants from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to help meet those challenges.

Mohsenin received a $100,000 grant from the NSF to develop signal processing architecture to detect seizures. The award of $150,000 to Slaughter from the foundation was to pursue work on nanoelectric probe arrays.

When patients are in a hospital, they often are connected to a myriad of monitoring devices. Outside the hospital, however, it is more difficult to monitor for important warning signs of distress.

Research pursued by Mohsenin – an assistant professor of computer engineering at UMBC – aims to develop monitoring devices and systems as good as those provided in a hospital.

Mohsenin runs UMBC’s Energy Efficient High Performance Computing Lab. Working with professor of computer science and electrical engineering Tim Oates and researchers at the University of Maryland Medical Center, she is developing wearable monitors to detect when someone is having a seizure no matter where they are.

A wearable seizure monitoring and alerting system could provide greater independence for patients with epilepsy. The technology available at present is bulky and uncomfortable. “There are not very efficient devices for people who suffer from epilepsy or those people whose epilepsy cannot be treated with medication,” Mohsenin says.

What Mohsenin envisions is a monitor with a comfortable headband that would measure EEG signals, and an arm band that would contain an accelerometer and could measure other signals such as pulse.

Mohsenin and Oates are working on a variety of representations and machine learning algorithms to extract useful information from multi-physiological signals for such a device. The amount of computation the devices have to do is daunting, she says.

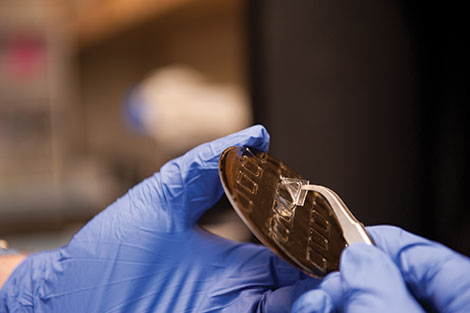

On the same floor of UMBC’s Information Technology and Engineering Building, Gymama Slaughter, an assistant professor of computer science and electrical engineering, is exploring how nanotechnology might produce a device that can monitor brain activity without risk.

A key problem in monitoring brain activity is physiological. To place brain monitors on a patient requires major surgery. It is a process fraught with peril.

In the Bioelectronics Lab she created from the ground up at UMBC, Slaughter is working in the nanoscale on artifacts so small they are at molecular or near molecular levels. The brain monitoring device she is working on is like a pyramid, literally one cubic millimeter in size with a tip pitch of 20 nanometers. (A millimeter is 4/100th of an inch.)

She is using gold for the device because it is an excellent electrical conductor, perfect for measuring electrical activity, and yet causes no adverse reaction in the body.

The neurosensors will collect data on brain activity, including what happens when a patient deals with Parkinson’s disease, strokes, epilepsy, brain damage, or Alzheimer’s.

“It might eventually measure how people behave,” says Slaughter, who also recently received a prestigious faculty early development award from the NSF. “What happens in the brain during anger, jealousy, or sadness?” It may also help understand researchers understand brain disorders such as obsessive compulsive disorder.

– Joel N. Shurkin

ON THE TRAIL OF TRUTH

In 2008, Jeffrey Davis, associate professor and chair of UMBC’s department of political science, published Justice Across Borders: The Struggle for Human Rights in US Courts (Cambridge University Press). The book made a keen impression on the field. William J. Aceves, a professor at California Western School of Law, called Justice Across Borders “an indispensable and innovative contribution to the study of human rights and the growing literature on international justice.”

In 2008, Jeffrey Davis, associate professor and chair of UMBC’s department of political science, published Justice Across Borders: The Struggle for Human Rights in US Courts (Cambridge University Press). The book made a keen impression on the field. William J. Aceves, a professor at California Western School of Law, called Justice Across Borders “an indispensable and innovative contribution to the study of human rights and the growing literature on international justice.”

Davis’s new book, Seeking Human Rights Justice in Latin America: Truth, Extra-Territorial Courts, and the Process of Justice (Cambridge University Press), will likely cement his status as a leading figure in human rights studies. It is a compelling study of what Davis calls the “twisted path” that justice follows when survivors and families of victims of human rights abuses in countries like El Salvador, Guatemala and Peru come up against a “thicket of impunity” in their judicial systems at home and take their cases to courts and bodies outside their national borders.

Davis shows “how secret dossiers, moldy police files, and clandestine communiqués are being pieced together” to do battle with “the many-headed monster that obstructs the search for justice.” And the dozens of redacted CIA memos and State Department cables cited here give the volume a haunting quality. But the heart of Davis’ story is the restoration of human dignity that drives victims to pursue justice. “As long as that dignity remains unrestored,” Davis maintains, “the risk of more violence exists.”

Q: What you call “the right to truth” figures prominently in your argument. What is that?

A: The right to truth grew out of a demand by families of the disappeared to know the whereabouts and fates of their loved ones. Often the intent of human rights violators is to erase the victim from society and to create terror and anxiety among the survivors. Truth overturns this intent. Courts have recognized the right to truth to be a universal and fundamental human right, enshrined in treaties and customary international law, because without truth there can be no meaningful justice. The right obligates states to conduct a full investigation and inform the families about the violations committed against their loved ones as well as the motives for those violations. It also requires states to publicly reveal their findings and return the victim’s remains.

Q: One woman interviewed for the book observed that the process of justice was “not just about punishing the people responsible for these crimes but also about the way that we live our relationship with the dead and the disappeared.”

A: Too often we think of justice as a result – a guilty verdict or a prison sentence. When you look at those who work for human rights justice in places with entrenched impunity, you see that justice means something more – it is a process with many important steps along the way. Certainly, it might include a guilty verdict, but that’s only part of it. For victims and their families it also includes the experience of sitting in a courtroom and telling their story. It includes the official acceptance of the truth, public apologies, and the return of the victims’ remains, among other possible elements in a complex process.

– Danny Postel

POWER DOWN

It has been close to two decades now since the concept of “e-government” began to sweep through city halls and county seats across the country. Proponents trumpeted the possibility that putting information and services online would revolutionize government, not only increasing its efficiency and effectiveness but spurring citizen input and activity in its proceedings.

It has been close to two decades now since the concept of “e-government” began to sweep through city halls and county seats across the country. Proponents trumpeted the possibility that putting information and services online would revolutionize government, not only increasing its efficiency and effectiveness but spurring citizen input and activity in its proceedings.

Donald Norris – professor and chair of UMBC’s public policy department – didn’t believe the hype. Change comes slowly and incrementally in government organizations, he argues. He was downright skeptical about claims of a cyber-revolution in government.

But as a good social scientist, Norris knew his hunch was not enough. So he decided to research e-government further. In 2011, following up on his earlier e-government research, he conducted two nationwide surveys of local e-government in the United States, eventually writing about his findings with Christopher Reddick, professor and chair of the Department of Public Administration at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

What Norris and Reddick concluded was that American local governments did adopt e-government models and practices rapidly. The problem was that they weren’t using those tools to do much more than save paper that they once used for press releases, mailings, and manuals.

“There’s an awful lot of information that governments put out through the web, but it’s like a bulletin board,” Norris says. “You can go to it, you can look at it, and you can download it and that’s pretty much it.”

In an article published in the journal Public Administration Review (“Local E-Government in the United States: Transformation or Incremental Change?”), Norris and Reddick argued that a key promise of e-government advocates went unfulfilled because the movement has resulted in very little interactivity between governments and citizens. They also noted that few policy changes have occurred as a result of the e-government wave.

“The cyber-optimists said people will come flocking to governmental websites to get governmental data, to interact with governmental officials, and to learn about policy,” Norris observes. “People don’t do that. They get excited when there’s an exciting issue or candidate, or if somebody is going to build a gas station in their backyard, but most of the time people aren’t interested in interacting with government.”

Norris does see some positive changes from e-government, including easier and faster access to public information. Lengthy budget documents can now be obtained online (as can driver’s license renewals), and citizens can fire off opinions to city councilors or county executives by email in a matter of seconds.

“It’s improved efficiency,” Norris says. “It’s also lowered cost in some areas. If you can get people out of line and online, the amount of staffing that you have to have at the front desk is reduced.”

So what is the future of e-government in the United States? Norris says that based on current evidence, the revolution may have stalled.

“My prediction was that in 2020 it will look pretty much like it does today,” Norris asserts. “There will just be more of it. It will not be interactive or any more transactional than it is today.”

– Max Cole

STEPPING UP

UMBC is known for the diversity of its student population – and the university is taking active steps to ensure that the ranks of its faculty become equally diverse.

UMBC is known for the diversity of its student population – and the university is taking active steps to ensure that the ranks of its faculty become equally diverse.

One of the most exciting initiatives to make that happen is UMBC’s Postdoctoral Fellowship for Faculty Diversity – a two-year residence program that offers promising scholars who are committed to diversity in the academy substantial support to prepare them for possible tenure track appointments at UMBC.

Fellows selected for the program are provided with teaching and research mentors and encouraged to participate in multiple professional development opportunities across campus. Recipients also receive tangible support in the form of a stipend, health benefits, and additional funding for conference travel and the preparation of scholarly work.

“UMBC recognizes the challenges that American universities face in recruiting and supporting a diverse professoriate,” says President Freeman A. Hrabowski, III. “We are tackling that challenge head on through this fellowship, while also extending our commitment to inclusive excellence.”

The current cohort of three scholars recruited to the program in 2013 – Kara N. Hunt (media and communications studies), Rwany Sibaja (history) and Evelyn Kamaria Thomas (mathematics and statistics) – hope to follow in the footsteps of Viviana MacManus – a member of the 2011 cohort who was recently named as an assistant professor of gender and women’s studies at UMBC.

MacManus received her Ph.D. at the University of California, San Diego, in the department of literature in 2011, and she is delighted that her fellowship has led to the appointment.

“I feel welcome and wanted here,” observes MacManus. “The warm and supportive community within the department of gender and women’s studies was a major reason why I stayed at UMBC. I felt supported intellectually, community-wise on campus, and personally. I had the support that I needed to succeed.”

UMBC provost Philip Rous says that the fellowship is already starting to achieve its main goals, and that the university will select the next cohort of fellows for the program in the coming year.

“The program allows the UMBC community to benefit from the presence of outstanding young scholars who bring their diverse backgrounds and perspectives to invigorate our scholarship and enhance the education of our students,” says Rous. “We also believe that this program will help us attract to UMBC the next generation of outstanding faculty and to enhance the diversity of our scholarly community to better serve our students and our local and global communities.”

MacManus says that the support she received was also a key element in the transition from fellow to faculty member. “The fellowship gave me time and support to transition from graduate school to the faculty,” she says. “ I designed my own classes, but also had the time to do my own research. I learned how to balance that, which I think is hard for new faculty right out of graduate school.

“I think I’m super fortunate,” concludes MacManus. “I keep telling everyone that I think I won the jackpot.”

– Richard Byrne ’86

Tags: Winter 2014