Develop and Displace

It’s rare that an author’s first book is hailed as a “trailblazing piece of scholarship.” Yet Rumor, Repression, and Racial Politics: How the Harassment of Black Elected Officials Shaped Post-Civil Rights America (University of Georgia Press, 2012) by George Derek Musgrove ’97, history, an associate professor of history at UMBC, received raves for its exploration of a paradox that has cast a long shadow over American political culture.

“Just as the Civil Rights Act of 1965 allowed for the desegregation of American politics and the election of a black President in 2008,” Musgrove observes, “so too did it lead to the rise of a racially conservative Republican Party and the repression and later disproportionate investigation of black elected officials. One cannot comprehend post-civil rights era American politics without understanding this contradiction.”

Musgrove has now turned his gaze to the shifting racial landscape of Washington, DC. In a series of articles co-authored with historian Chris Myers Asch (and a book, Chocolate City: Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, to be published by the University of North Carolina Press next year), the duo examine the decades-long process of gentrification that at last erased the city’s long-held black majority status in 2011.

In articles published in The Washington Post and in the forthcoming anthology, Capital Dilemma: Growth and Inequality in Washington, D.C. (Routledge), Musgrove and Asch observe that “[f]rom our pulpits and papers to our blogs and barbershops, Washingtonians are grappling with a city that is becoming younger, wealthier – and whiter.”

Yet the “burst of development and displacement that has fundamentally changed the physical, demographic, and political terrain of the capital city” is “far more complicated” than the pervasive narrative in which gentrification is merely a revival of city neighborhoods gutted by major riots in 1968.

Examining changes over the lifetime of Washington resident Louise Thomas, Musgrove and Asch observe that “[R]eal estate agents, developers, lenders, landlords, and new residents had taken advantage of historical, state-sanctioned under-development of black communities to make money off of her homes. Only the determined struggles of residents, aided at times by the city government, had allowed people like her to stay in place. Most of her old neighbors, however, had been swept away.”

Musgrove says that, at one level, “narrative does not matter much at all in a struggle over property” in the District. “Black folks have been screaming for years that the city and much of its most famous culture is theirs,” he explains. “And many new residents have said, in effect: ‘Totally agree. Now get off my stoop.’

“That said,” continues Musgrove, “as a historian, I care a great deal about narrative and think it plays an important political role. The narratives we tell about ourselves and others have impacts on our politics.”

Musgrove says it might take some time: “In a perfect world, I would like to believe that someone from the city council will pick up my article, get the idea that the city council has done and can now do something to slow displacement – not just build new projects for the existing poor but slow displacement in the private market – and do it. But I’m not holding my breath.”

– Danny Postel

Turning the Tides

Even as a teenager, Lorraine Remer was fascinated by weather, tides and currents. At UMBC, she has made a career forging those key elements of climate into compelling research and a new business.

Remer, who is now a research faculty member in physics and at UMBC’s Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology (JCET), recalls jumping at the chance to participate in the Mariners – a branch of the Girl Scouts launched in the early 1930’s focused on the sea and maritime sciences.

Eventually Remer’s interest in these forces and their effect on our environment led her to enroll in the atmospheric science program at the University of California, Davis, where she first obtained a B.S. and then her Ph.D. in the discipline. “I was looking for an environmental science that was hard science,” she says.

Discovering the precise mathematical language to create weather maps or accurate pictures of the sky also impressed Remer. “The fact that you could represent what was going on in the atmosphere with math equations was just amazing,” Remer recalls.

Math’s simplicity is a boon that allows scientists to describe very complex things succinctly, she observes: “It takes a lot of words to describe the movement of a fluid, but I can write an equation and do it very simply. It’s elegant.”

Her continuing interest in the interactions between air and sea led Remer to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego to research and obtain a master’s degree in that field as well.

In 1991, Remer was hired at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, working as the protégé of legendary NASA scientist Yoram Kaufman.

Remer’s interest in the effects of aerosols on climate mirrored those of Kaufman, and she worked with him on algorithm development for the aerosol products on the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensors carried on the Terra and Aqua satellites. The MODIS sensors provide key environmental data on the health of our climate.

Kaufman’s untimely death in 2006 was one factor in Remer’s decision to leave government service and take a position with UMBC at JCET in 2011. Another factor was her desire to become more involved in the entrepreneurial side of research. Remer’s first job in the private sector was at a Sacramento-based company called Atmospheric Research and Technology, and she had always been impressed by the example of Ed Berry, who successfully started the company at the height of a recession in the 1980s and actually created jobs with research.

Joining JCET has allowed Remer to follow in Berry’s footsteps and do something that had been on her mind for a long time – start a company. Her business, AirPhoton, was started with co-founder and fellow UMBC researcher Vanderlei Martins, professor of physics. Not only does it design aerosol sampling instruments, but it also provides customized instrument design, satellite data analysis, and remote sensing algorithm development.

Remer’s work at UMBC isn’t all business, however. Her research interests at JCET remain rooted in her early love of climate science. She is particularly interested in the interplay between man-made land surface changes and particles in the atmosphere.

“I think it’s really interesting,” she muses, “the effect people have – and have had – on this planet.”

– Nicole Ruediger

Far from the Opry

It’s nearly impossible these days to turn on a country music station without hearing the voices of “new country” stars Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, or Carrie Underwood – and pretty much nothing else – blasting through your car speakers.

A national playlist has been the norm since the 1950s, when Nashville became the de facto center of the business side of country music. But it wasn’t always that way. In its infancy, before the Nashville sound took hold, country was a regional music with any number of different sounds and centers.

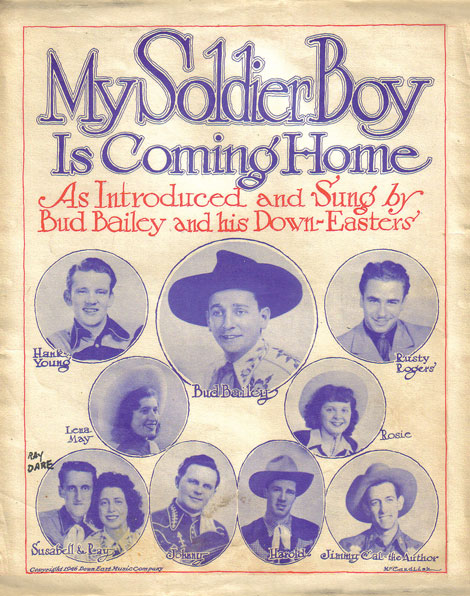

Indeed, some of those regions might surprise you. Clifford Murphy, an adjunct lecturer in American studies, has spent the past decade researching country and western music in his home region of New England. The New Hampshire native and ethnomusicologist recently published his findings in a new book: Yankee Twang: Country and Western Music in New England (University of Illinois, 2014).

“Historically, when people talk about country music and why they like it or don’t like it, they’re talking about recordings and commercial products,” observes Murphy. “I think that’s really looking at it wrong. Country music in its origins started out as working-class, community music. It was this stylistic compromise among city people, rural people, and people of different ethnic and racial backgrounds.”

Murphy focused on New England not only because of his own deep ties to the region and his love of its particular brand of music. He also wanted to make a tangible contribution to the excavation of country and western music’s rich past. One thing Murphy discovered in his research was that country music was not immune to the larger implications of the arrival of television in the 1950s, which changed the way people socialized and interacted with their neighbors.

“It’s not just country music. I think places like grange halls disappearing and falling out of use says a lot,” says Murphy. “These grange halls, churches, and other places of community were places where people got together for events, and that has really dropped off. It’s not that they don’t listen to music, speeches, or events, but they’re doing it in isolation from one another and I think that’s worth reflecting on.”

Murphy’s book delights in revisiting a past where New Englanders could go to hear indigenous country music far from the South and West with which it is usually identified, and revel in celebrating their own local heroes of the genre.

“I hope people get a sense that they can go out and find remarkable local individuals who can connect them to their heritage, explain the things that they don’t see right in front of them, and can be their guide to their own cultural landscape,” Murphy says. “That’s an amazing experience.”

– Max Cole

Prize Fighter

Six years ago, the very first issue of UMBC Magazine featured the legendary political cartoonist Kevin Kallaugher (better known as “KAL”) and his tenure as an artist-in-residence at UMBC on its cover. Given Kallaugher’s prolific energy and talent, it’s little surprise that he is ending his time at UMBC with a bang.

Kallaugher started the year as the recipient of two of the world’s major cartooning awards – the 2015 Herblock Prize and the 2015 Grand Prix Press Cartoon Europe. (He will pick up the latter award at the July 4 opening of the 54st International Cartoon Festival in Belgium.)

“I feel I get an award every day when I wake up in the morning and go to ‘work,’ where I’m doing something artistic and also addressing the very important issues of the day,” quips Kallaugher. “Plus,” he adds with a chuckle, “You’re venting your spleen.”

The Herblock Prize panel cited Kallaugher’s “ability to jump between macro-international policy issues to Baltimore mayor’s stonewalling about the accuracy of its speed cameras.” The cartoonist has used his time at UMBC to execute a similar leap in form, expanding his horizons from his honored work in traditional cartooning at The Baltimore Sun and The Economist, into new vistas of animation in collaboration with the university’s Imaging Research Center.

“When people would ask me about the future of cartooning, I would always say it lies with animation,” he explains. “And I would tell them about UMBC, its great reputation and so forth. So when an opportunity came up, because I was leaving The Baltimore Sun, the first place I thought of was UMBC.”

In late April, the university will host a special KAL lecture on one of the most divisive and controversial topics in his field: “The Future of Cartooning after Charlie Hebdo.”

As a noted civil libertarian and past president of the human rights group Cartoonists Rights Network, International, Kallaugher has mixed feelings about the environment in which cartoonists currently work.

“For cartoonists and satirists, it’s the best of times and the worst of times,” he says. “It’s the best because more people around the world are viewing cartoons than ever before, and satire is making a resurgence. It’s the worst because it’s never been more dangerous to do what we do.”

Kallaugher’s latest projects include creating images of Edgar Allen Poe for The Raven Beer brewery and a planned series of animated shorts about the 2016 presidential election. He adds that he has tremendous affection for UMBC and its students and scholars, with whom he collaborated on projects including a political education website, USDemocrazy.

“It’s intoxicating to be in this wonderful environment where there is so much positive energy,” he explains, “and where someone like me has an opportunity to share a lot of our accumulated wisdom. That experience is so rewarding!”

– Hussein Ibish

Tags: spring 2015