UMBC’s growing reputation as a hub for research with powerful impact isn’t founded on the achievements of renowned scholars who have created laboratories or explored the limits of the arts, humanities and social sciences at the university alone. It is also built on a growing number of impressive younger scholars who have found a home for their work at UMBC.

The pedigree of the scholars who will propel research and teaching at the university in its next 50 years can be measured in part by the number of early career teaching and research awards these up-and-coming faculty members have received.

One of the most prestigious of these honors is the National Science Foundation’s Early Career Development (CAREER) award, which was created to support “junior faculty who exemplify the role of teacher-scholar through outstanding research, excellent education, and the integration of education and research within the context of the mission of their organizations.” UMBC faculty members have received 29 NSF CAREER awards over the last two decades.

UMBC Magazine would like to introduce you to some of the faculty who represent the bright future for research and teaching at UMBC – and how they are already making their mark on academia and the world.

Christopher Hennigan

Everyone dreads a bad air day when it pops up on a weather forecast, but knowing how those conditions are created is essential to finding ways to ameliorate or prevent the damage to health and climate.

Christopher Hennigan, assistant professor of chemical, biochemical, and environmental engineering, is at the forefront of analyzing these issues. His work focuses on pollutants known as particulate matter or aerosols—small particles in the air that have detrimental effects on human health and important implications for climate change.

This work has come to the attention of the National Science Foundation (NSF), which gave Hennigan a CAREER award of $524,606 to characterize the effects of acid-catalyzed reactions on the atmospheric transformation of volatile organic compounds into secondary organic aerosol (SOA).

SOA is an ubiquitous component in the atmosphere that contributes to aerosol effects on human health and climate, but there has been disagreement between laboratory studies and ambient readings on the role of particle acidity in its formation. So Hennigan and his team are developing new methods to rapidly measure particle acidity through automated system that provides the best combination of high time resolution and accuracy.

When Hennigan’s new technique is deployed, it will provide more accurate models representing SOA formation, thus improving scientists’ ability to make predictions related to ambient aerosol events.

“The five-year duration of the CAREER award is especially advantageous, as it will allow us to push the work forward in a highly significant way,” says Hennigan.

–Dinah Winnick

Danielle Beatty Moody

Can poverty and discrimination lead to accelerated diseases and disorders related to the brain including stroke, dementia, and cognitive decline? Pronounced racial disparities have been observed in studies of brain health and pathology, but little is known about how social disadvantages over a lifespan may contribute to those outcomes.

Danielle L. Beatty Moody, an assistant professor of psychology, won a $600,000 Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2014 to investigate these disparities in brain health for African Americans, taking into account many of the possible causal complexities.

As primary investigator of the project, Beatty Moody works with nearly 300 Baltimore residents to determine if there is a relationship between social disadvantages early in life and MRI-indicators of brain pathology that predict future strokes and overall cognitive decline. Her work also examines if these combined factors are more pronounced in African American adults than they are in white adults.

“This type of study has really not been done before,” explains Beatty Moody. “We have a diverse sample in our study, considering race, ethnicity, and a range of socioeconomic statuses.”

Beatty Moody will also investigate associations these data might have with risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The goal of her research is to develop appropriate prevention and intervention strategies that can reduce – and ultimately eliminate – race-related health disparities.

“The key is to understand how early life adversity and race and ethnicity interact to form the health disparities we see in adulthood with African Americans,” Beatty Moody says. “A lot of what happens in childhood can be hard to undo.”

–Max Cole

Felipe Filomeno

Why have some countries taken relatively corporate-friendly approaches to intellectual property rules, while others have been more resistant to corporations’ desires? Felipe Filomeno, an assistant professor of political science, spent half a decade studying those questions in South America. Last year, his research led to an Early Career Prize from the Latin American Studies Association.

As a student, Filomeno became intrigued by the disputes surrounding Roundup Ready soybean seeds, a genetically-engineered product introduced by the Monsanto Company in 1996. The seeds generate easy-to-grow crops that are resistant to herbicides, but Monsanto has fought for widely-disliked laws that forbid farmers from saving, trading, or cross-breeding patented seeds.

In some countries — notably Brazil — Monsanto has won almost all the legal protections it has sought. In Argentina, for example, farmers have maintained the right to save and recultivate seeds from their own soybean crops, including seeds that have inherited Monsanto’s engineered traits.

“I thought [these differences were] an interesting and understudied issue,” says Filomeno, who spent several years doing field work, archival research, and interviews while he was earning a doctorate in sociology at Johns Hopkins University.

In Monsanto and Intellectual Property in South America (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), he argued that Argentine farmer-activists’ success derives largely from the fact that the nation’s major farmers’ organizations were given formal roles in regulating agricultural biotechnology as early as the 1970s.

Since arriving at UMBC in 2014, Filomeno has researched how cities make conscious efforts to welcome immigrants. He has spent the past two years studying ostensibly pro-immigrant municipal policies in Baltimore and other U.S. cities, and is now examining immigration policies in Buenos Aires, Mexico City, and Sao Paolo.

–David Glenn

Jeffrey Gardner

Simple biological processes can have great impacts. They may even be the future of fuel.

Jeffrey Gardner, an assistant professor of biological sciences, investigates the soil bacterium Cellvibrio japonicas and how it finds and breaks down complex sugars for energy. He received the Department of Energy’s Early Career Award in 2015 to advance work that adds to foundational knowledge and may have practical uses in renewable fuel.

Gardner is especially interested in how C. japonicas may prioritize one energy source over another. “If you’re a bacterium in soil, your senses are not as sophisticated as ours,” observes Gardner. Yet the microbe at the center of his research is able to regulate production of enzymes that break down nutrient sources depending on which are present and “move toward things they like and away from things they don’t.”

Part of Gardner’s work focuses on engineering C. japonicas to produce bio-ethanol as a source of renewable fuel. He recently submitted his first patent application. “It’s exciting to translate the research into a product,” he says.

While the applications are exciting, Gardner says the foundational knowledge his research provides is crucial. “Getting people to find value in fundamental science is incredibly important,” he says.

Gardner adds that UMBC’s biological sciences department “really wanted to make sure my research program took off. A lab is like a spaceship: It takes a really long time to get to the launch pad, and a whole lot of fuel to lift off, but once you’re in orbit, things get a little easier.”

–Sarah Hansen

Viviana MacManus

The human cost of conflicts in Latin America in the latter half of the 20th Century was immense – so much so that the political violence in places including Mexico and Argentina became fixed in the public imagination as so-called “dirty wars.”

Viviana MacManus, assistant professor of gender and women’s studies, has focused much of her research on uncovering the legacy of those conflicts. It is research that has been recognized by the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation with a Career Enhancement Fellowship for Junior Faculty award.

Funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the award provides support to junior faculty to pursue scholarly research and writing essential to attaining tenure. MacManus will use the sixth-month fellowship to work on her book manuscript We Are Protagonists of This History: Gender, Political Violence, and Testimonies of Resistance in Latin America’s Dirty Wars.

MacManus cites the “support network and sense of camaraderie” at the university as a key to “helping junior faculty thrive and succeed in their careers at UMBC.”

Her book is largely based on research she conducted in Argentina and centers on gender and state violence during the violent political tumult in the region in the two decades after 1960. MacManus is compiling extensive interviews she conducted into oral histories that examine the gender politics involved in guerrilla movements and unarmed political organizations in Mexico and Argentina.

“I am pleased that there is investment in supporting academic work on social justice scholarship and feminist theory,” says MacManus, “as my research focuses on critical human rights and gender violence in Latin America.”

–Max Cole

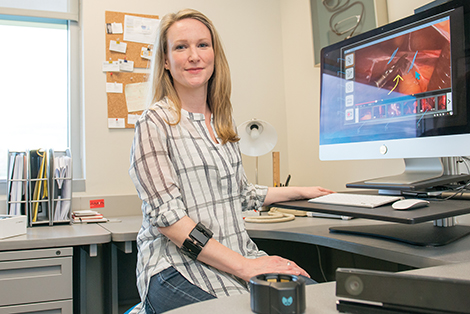

Helena Mentis

Physicians, and specifically surgeons, have a wide array of new technologies to help them perform faster, safer procedures. But how can they be utilized while maintaining core principles of surgery – especially ensuring sterility?

Helena Mentis, assistant professor of information systems, is pushing that careful balance of innovation and tradition with work that focuses on “touchless interaction” interfaces. The technologies that Mentis uses in her lab are commercially available, she explains, and surgeons can wear the devices under their scrubs. She began her research using Xbox Kinect, then eventually moving to Leap Motion. Most recently, she has worked with the Myo armband and Google Glass.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) saw the potential in Mentis’ research on surgical telemedicine and gave her a $518,121 CAREER award to explore the benefits of collaborative image interaction through gesture-based tools. Such tools will allow remote surgeons, for instance, to share their expert knowledge in the operating room.

Finding the right tools and best practices to most effectively facilitate telemedicine, teleconsulting, and telementoring will be at the center of Mentis’ research. She will also investigate verbal and nonverbal mechanisms that medical professionals use to share knowledge and images quickly, while avoiding contamination in the operating room.

Mentis observes that telemedicine is often considered the future of medicine. But though there are many promising technologies now available, she adds, “there are no clear directions yet about the best ways to do telemedicine.”

Over the course of the grant, Mentis hopes to incorporate new emerging technologies into her research and help shape the direction telemedicine will take as it becomes a common tool in medical practice.

–Megan Hanks

Corrie Parks

Most animation is created digitally, but Corrie Francis Parks – an assistant professor of visual arts – prefers to handcraft colorful work such as her short animated film, “A Tangled Tale,” using materials including sand.

“We’ve been through the digital revolution,” says Parks. “We’ve achieved photo realism. What comes next? What comes next is artistry.”

“A Tangled Tale” has been shown at film festivals around the world – one of a series of projects that is bringing Parks international acclaim. Her new book, Fluid Frames, was published in April, and features some 30 pioneers in experimental animation, and her tour for the book included a stop in Vienna, Austria.

In March, Parks and UMBC associate professor of visual arts Kelley Bell ’06, imaging and digital arts created “Projected Aquaculture” – a whimsical look at the Chesapeake Bay – for the Light City Baltimore festival. This summer, the project will be screened on the facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, Croatia.

Parks was a freelance animator and photographer in Montana before joining UMBC’s faculty to teach stop motion and character animation two years ago. “It’s a really fabulous place to be a faculty member,” she says.

She appreciates that UMBC’s approach to research explicitly embraces the arts. “That’s the kind of environment you want to work in,” Parks says.

The students in UMBC’s broad liberal arts program have also proved to be an attraction to Parks ”They come up with things I couldn’t teach them,” she observes. “They just figure it out.”

–Mary K. Tilghman ’79

To see “A Tangled Tale,” go to corriefrancis.com.

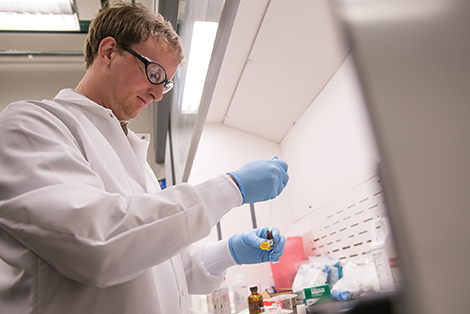

Matt Pelton

Nanoparticles are a key element of product design, so foundational research in understanding how they interact with the environment is crucial. Scientists understand how conventional liquids, like water, behave on ordinary time and length scales, and how individual molecules make up liquids, but there is less understanding about liquids on intermediate scales.

Matt Pelton, assistant professor of physics, is exploring liquids’ behavior at that scale. He has developed a method based on ultrafast laser spectroscopy of vibrating metal nanoparticles suspended in liquids to understand the complex properties and molecular interactions of ordinary liquids. It is work that not only has technological potential, but also advances our understanding of the function of biological molecules, which live in a liquid environment.

“It’s like ringing a bell, but on a much smaller scale,” says Pelton. The nanoparticles in liquids that Pelton studies vibrate a few billion times per second, and can be manipulated with laser pulses. These pulses cause the nanoparticles to expand and vibrate, but like a bell, they react differently depending on the liquid that they are in. Pelton is working to understand how long the nanoparticles vibrate when hit with laser pulses, and where the energy goes as the particle moves.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) recently gave Pelton a CAREER award of approximately $650,000 to advance his work on how mechanical energy flows at the nanometer scale. Pelton has also created a research group on campus, and says that he is committed to training the “next generation of scientists in an environment that emphasizes inclusive excellence.”

–Megan Hanks

Tags: Summer 2016