CENTER STAGE

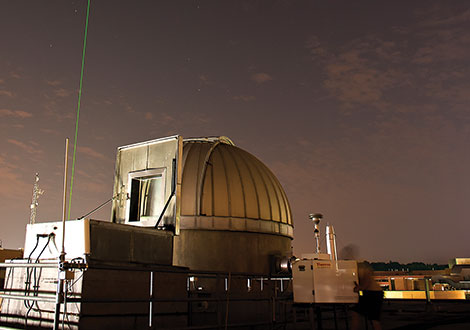

On a hazy day in Baltimore, Ray Hoff can tell you if the smog that you see is from the Midwest, from Quebec, or from Baltimore itself.

Hoff, a UMBC professor of physics and senior science advisor to the Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology (JCET), began his career at Environment Canada with two projects: studying the deposition of toxic chemicals in the Great Lakes and looking at particle concentration in the atmosphere using a laser technology called LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) to take those measurements.

When Hoff moved to UMBC in 1999 to become the director of JCET (a collaborative center run by UMBC and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center), he abandoned chemical research to concentrate fully on efforts using LIDAR. Yet Hoff’s desire to use research to explore environmental concerns never waned.

“I remained interested in thinking about what kinds of things a physicist could apply to environmental problems,” he recalls.

Hoff’s thinking eventually took the shape of what’s now known as the “Smog Blog” – a website he started with Jill Engel-Cox, ’04. Ph.D., marine estuarine environmental science, in 2004. The website merges real-time satellite imagery and air quality data with analysis of air pollution across the United States for people interested in air quality. It’s been a tremendous success, logging more than 50 million hits during its first eight years.

Hoff’s arrival helped boost UMBC’s research culture by expanding its funding base. “The university,” he says, “was hungry to increase its research portfolio.” So Hoff got to work. During Hoff’s tenure as JCET director, the university brought in $130 million to be spread out over 10 years for GEST (Goddard Earth Sciences Technology Center) from NASA, and an additional $18 million for JCET which was spread out over five years.

These centers brought significant research dollars to the UMBC between 2000 and 2005. And with that funding came recognition. From 2001 to 2005, UMBC ranked third in the number of published earth science citations according to an analysis by Thompson-Reuters (ISI).

“These research centers were critical in helping transform UMBC to a research class university,” Hoff says.

This year Hoff won the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal for the use of satellite data in the study of pollution and bringing public awareness to NASA research for projects including the Smog Blog. Hoff joined such luminaries as Carl Sagan and Robert Heinlein in receiving the prestigious award.

At the end of June, Hoff will retire from UMBC to pursue other interests while also keeping a hand in science research. One of his activities may come as a surprise after a career spent using lasers to help study the skies.

“I’m thinking of writing a book on the Spanish Civil War,” he says.

– Nicole Ruediger

COMMUNICATING WITH COLOR

Animals have all kinds of ways of communicating – colors, smells, sounds, dances. Indeed, the diversity of communication channels can make it difficult to figure out exactly why animals make the choices they do.

“Most of the time, we don’t know why different species – such as cardinals and blue jays – don’t mate with each other,” says Tamra Mendelson, an associate professor of biology at UMBC. “Is it because they’re different colors, or because they have different songs?”

The streams of Kentucky may just have an answer. Mendelson and a UMBC graduate student, Tory Williams, work on two closely-related species of small fish, called darters, which are found in the waters of that state. Like many animals, including birds, male darters are brightly colored. Female darters have a drab brown color.

Darters can’t communicate with song, so Mendelson and Williams hypothesized that female and male darters may base their mating preferences on the coloration of the opposite sex in their species.

“There are many examples where you have groups of closely related species that seem to differ almost exclusively in color,” says Mendelson. “And it’s almost always the males that express this color. So the default assumption is that when they’re together in nature, the females are attracted to the colors of their own species and that’s how they tell each other apart. But really there’s been pretty poor evidence for that.”

To test the idea experimentally, the researchers selected two species of darters (one with reddish males and one with greenish males) and then built color models of them. These “fish decoys” – which look something like a fishing lure – were attached to a long stick that was rotated back and forth using a motor to simulate swimming behavior. Each model was then placed on the opposite end of a tank from the other behind a plate of glass.

Eventually, a real female was added to the tank and allowed to acclimate. The fish would then make a selection. Mendelson and Williams found that each darter in their experiment selected the model of the opposite sex that most closely represented its own species.

Using models of darters instead of actual fish ends up playing a key role as a control for the experiment. “If you were to use live fish to see if a female was attracted to a live green male or a live red male,” explains Williams, “you couldn’t control for how those males decide to behave.”

The researchers say that the study tells us just as much about how animals think as it does about how they mate. The darters’ colors, for instance, may have evolved due to different evolutionary pressures and could convey different information. The red coloration might reflect good diet. The green color might express good camouflage.

“We think of colors as their own specific language,” says Mendelson. “So each species has a different language.”

Williams agrees: “We learned that these colors have a biological role in these fish. The fish see these colors and they are meaningful to them.”

– Nicole Ruediger

NOW HEAR THIS

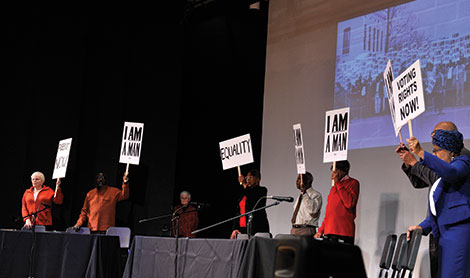

When UMBC’s Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture (CADVC) brought its award-winning exhibit For All the World to See back for a triumphant return to campus after a national tour, the center also extended the reach of the project beyond those images and into another realm: storytelling and oral history.

This affiliated project, titled For All the World to Hear: Stories from the Struggle for Civil Rights, was created as a collaboration between CADVC and Heritage Theatre Artists’ Consortium founder Harriet Lynn. The project was curated by Sandra Abbott, the CADVC’s curator of collections and outreach, and it received funding from the Maryland Humanities Council.

Lynn recruited veterans of the Civil Rights movement to tell their stories on stage, seeking them out via advertisements in publications read avidly by seniors in the Mid-Atlantic region.

“I was looking for diversity,” Lynn says. “Different voices. Some actively engaged in the Civil Rights movement, and others who were supportive of it.”

The participants whom she gathered together shared deep personal connections to the movement. Robert Houston is a photographer who covered the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign for Life magazine. Patricia Brown Leak, a former music educator in Washington, D.C., talked at length about her family’s involvement with the movement – and specifically the prominent role played by her brother, H. Rap Brown, who was head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Minister of Justice for the Black Panther Party. Another member of the performing troupe, Deryck Charles, was born in South Africa, studied at Cambridge University, and joined up with the Freedom Rider movement in 1961.

“We were very lucky to get the wonderful people we got,” Lynn observes.

Many of the stories told by the project’s participants – augmented by song and simple props – recounted the small indignities and insults of an American society steeped in racism and unwilling to change its ways. Yet as For All the World to Hear built to its climax, the participants shaped their accounts of the brutality of the nation’s racism – and the determination required to overcome it – into intensely harrowing personal tales.

The price paid by some of the storytellers was heartbreaking. In a few vignettes, John and Shirley Billy recounted the story of his blossoming career as a singer and the almost instant love that John (a young black man from Washington, D.C.) and blue-collar Irish girl Shirley felt for each other upon meeting. But their subsequent marriage (which is still going strong after 54 years) and the birth of their son left the couple at the mercy of Maryland’s harsh miscegenation laws – which landed Shirley in jail and compelled them to place their child in an orphanage for a time.

These stories of police beatings and incarcerations and contempt and insult remain powerful and poignant despite the fact that America’s Civil Rights struggle – while continuing – has scored immense and important victories. By showcasing the voices of those who worked and suffered to win those victories unite in hope and song at the end of For All the World to Hear provides another window into the tragedies and triumphs of our shared history.

– Richard Byrne ’86

– Watch a video from For All the World to Hear here.

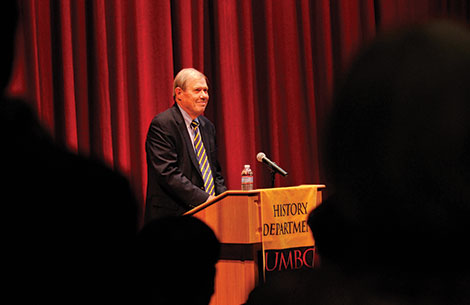

FAULT LINES

When disastrous events take place, it’s common to try to find a single person to hold responsible for failure.

“It was George Bush. It was Dick Cheney. It was Michael Brown. It was [British Petroleum]’s CEO,” says John Rennie Short, a professor of public policy at UMBC. “In other words, there was one person, a bad person, to blame.”

But Short urges caution in settling on singular scapegoats. In Stress Testing the USA: Public Policy and Reaction to Disaster Events (Palgrave Macmillan), he examines four major traumas the United States experienced from 2000 to 2010: the Global War on Terror, the flooding of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, the global financial meltdown, and the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

“The point of the book was to move beyond the surface appearance [of what caused each event], to move beyond the easy points of criticism, and to look for much deeper and more profound structural concerns,” Short explains. “I think we’ve missed some profound lessons if we don’t look at these things in some detail.”

Analysis of Katrina, for instance, reveals a chain of responsibility that includes local, state and federal elements. Environmental policies that led to the erosion of coastal barriers over 50 years set the stage for catastrophe. When the storm hit, Short explains, “it was not the hurricane itself that drowned New Orleans, but the failure of the levees.”

The idea of a stress test to assess stability or health is concept that is familiar from engineering and medicine. The application of pressure to a material or a human being can help reveal weak spots – preferably before any collapse. Short says that disasters can provide a similar test for larger elements of our political and economic infrastructure.

“Stress testing is really a form of looking at the effects of big pressures on a system,” observes Short.

In Stress Testing the USA, Short identifies specific structural flaws with the potential to fracture our nation: a large, active military that promotes a state of permanent war; an aging physical infrastructure with bridges and roads that receive failing grades; financial and corporate deregulation; and a blind acceptance of major institutions’ increasingly risky behavior.

Identifying these systemic problems also clarifies broader concerns for Short, particularly the problem of “cognitive capture.”

Cognitive capture involves paying attention only to what is immediately in front of us, to the detriment of the less clearly visible. In terms of disaster prevention, cognitive capture can mean sidelining unpopular perspectives or more subtle voices that might alert us to possible threats.

“There were people who argued that the invasion of Iraq was wrong, people who said that there was a housing bubble, people who said that the levees were inadequate, people who said that the oil drilling was becoming more dangerous,” Short emphasizes.

But as alarming as the disasters and structural problems in the book are, Short’s goal is not to simply scare readers; it’s to inspire action.

“Almost all these events were completely predictable when you look at the underlying structural flaws,” says Short. “For every event there was a small group of people who knew exactly what was happening, we just didn’t listen to them. So the point of the book is we should be more careful and more attentive to alternative, dissident voices.”

—Dinah Winnick

Watch a video interview with John Rennie Short here.

Tags: Summer 2013